The talented VFX artist talks to us about starting out in visual effects and where he’s going next.

Sean Lewis. Photo credit: Emily Usher

Sean Lewis is a VFX artist, based in London, working in film and TV. He trained in production level compositing and colour space methodologies, specialising in invisible fixes. He has focused on compositing but worked at many other stages of the VFX process from conceptualisation to final output (including 3D model building, lighting, texturing, multi-pass rendering & particles/asset creation) working for Flatcap Films, Bloodsugar Films for the BBC and award-winning short films. We had the chance to chat to him about his current and upcoming projects as well as his passion for the industry.

What first drew you to VFX work?

I would say it all started when I was fifteen years old and I made fan videos with my mate. We’d take anime and films and cut them to our favourite tracks for fun, probably making over seventy music videos between us. It quickly became apparent that I had a preference for visual impact and often tried to enhance shots with colours, glows, particles and other visual trickery. The first thing that made me consider VFX as a career was while watching The Matrix. It wasn’t, in fact, the bullet time stuff but a more modest scene, where one of the sentinels detects a signal as it moves past the Nebuchadnezzar ship. All of its legs fling out and an array of detection devices open up at once. I remember thinking “Wow, somebody had to sit there and think about what all those devices do, and how a machine like that would move”. That was really the moment when I became aware that VFX was something I could, and would, like to do. Although I’d already seen iconic visual spectacles like Jurassic Park, and even VFX breakdowns for Titanic by that point, I was still too young to imagine that I would ever have access to that kind of technology. In my mind it was all done in a far, far away place that I would never step foot in.

Who would you say are your biggest creative influences and why?

There have been so many. They have largely been people who actively tried to share their knowledge and experience and help the community, but also with interesting back stories. Allan McKay, who was a pyromaniac as a kid and now specialises in fire and explosions in Hollywood blockbusters. Also Caroline Pires who founded Nerdeo out of a need to have a stable base for VFX artists to help each other outside of big studios. Then there is Andrew Kramer who has taught hundreds of thousands of people. His work and developed intuition for the craft is amazing. But, unlike a lot of the greats, you get to see where it all started. You can see map of his journey and how he has improved and that’s an important thing to see as an aspiring artist because it makes you feel that you can do it too!

There is also Grant Warwick, an Olympic boxer, who, aside from training, spent night after night trying to understand how to make something look photorealistic and now immaculately summarises years of study into a couple of hours. One of the patterns here is that these are often “bedroom artists”, also like Gareth Edwards, who go from strength to strength as mavericks through their own originality and drive.

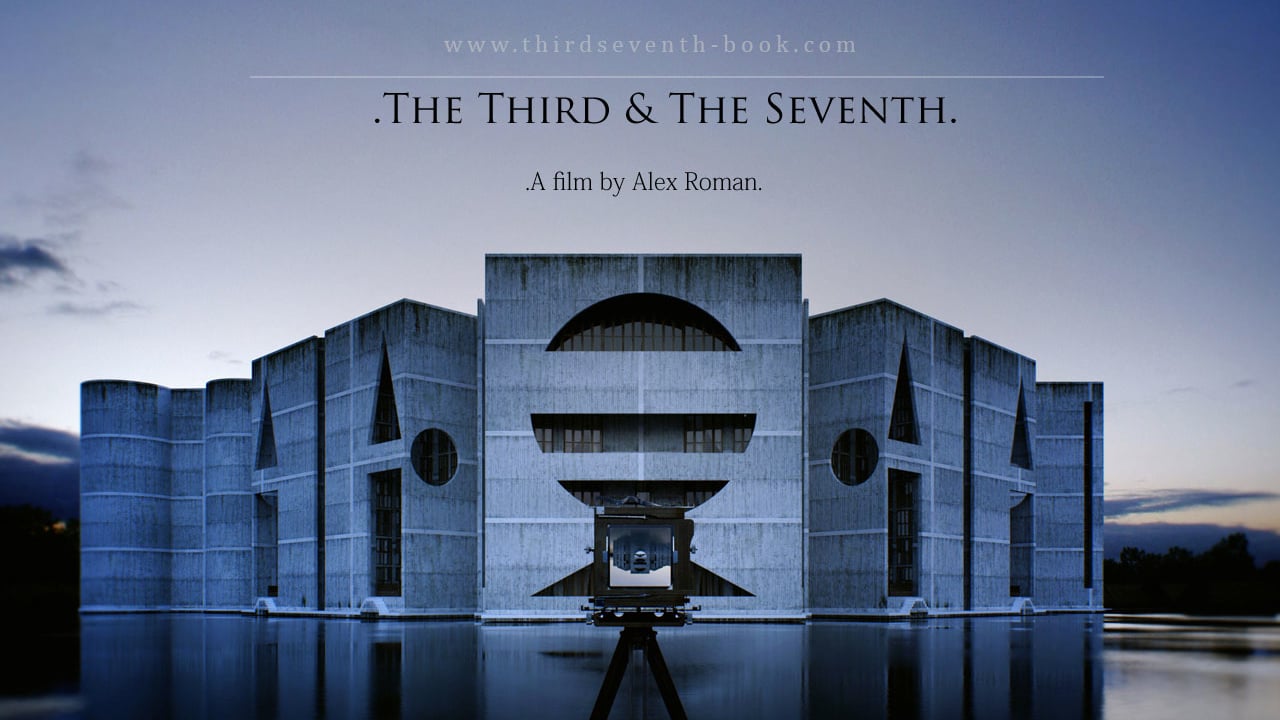

If I had to put someone at the top, though, for having the biggest direct impact, it would have to be Alex Roman. He is an artist who grew tired of the monotony and lack of imagination in the architectural visualisation world and made a beautiful film (The Third and The Seventh) to convey frustration and loneliness. That film made a huge impact on me. I would not have thought it possible that a film about buildings could make my eyes well up. Then at the end I realised he did it all himself. The quality of the work is impeccable and still holds its own against stuff being made all these years later. I think that was the moment I decided I was going to commit full time to visual effects.

What impact do those influences have on your work and your decision making?

All of the above people are curious and determined; they respect and appreciate how things work. They themselves work hard but it doesn’t seem to wear them down, it just makes them better at what they do. Those qualities helped change the way I approached the craft. When I started out I did a lot of work for free, but I had to think about what I was gaining in place of pay: experience, skills and credibility. I thought of it as if I was doing the equivalent of spending money on a course, except paying with my time, and learning how it was done in the real world. Eventually I gained a position where I was a bit more in control. As my technical understanding and initiative improved it enabled me to better assess the benefits and pitfalls of each project before choosing to take it on.

Can you tell us a bit about your latest project?

Outside of my day job in TV, I’m working on four different projects at the moment, including shooting two mini-series that are pitches for a pilot. These two are both more personal projects that I’m doing to keep my on-set practice well-oiled and give myself a better chance to gain work that I can both live off and have creative control over. For example, we are currently shooting the second episode of The British Dark, a paranormal series featuring Sylvester McCoy. I learned most of my guerilla VFX and filmmaking techniques making the first episode and it’s something I’m still proud of. There were typically four or five of us on set with entry level kit and we had to improvise significantly to raise the production value to something that looked like it had a budget of some sort. The other series is called Angel North, a sci-fi, set in the future, about a crew that gets flung into space following an explosion on the mothership, and how they cope.

I also work on independent film productions in my own time in order to make sure I stay fairly active in the film world. At the moment I’m working on a short film The Riot Act, as part of the Flat Cap Films collective, directed by Oliver-Riley Smith. It is loosely based on the London riots and told largely through voyeuristic/surveillance/social media platforms. The funding was raised though kickstarter.com along with some private investment. Another short I’m working on is Game Day, directed by Chris Roberts, a dystopian film set in the not too distant future. I have been designing CGI elements that are very sci-fi based, which is fun. I have a plan to get a team together to help me with compositing while I’m doing the CGI stuff, so it would be my first lead compositor role. The prospect is exciting and feels like a significant milestone.

VFX work can be quite a broad term and incorporates a lot of different disciplines. What does it mean to you, specifically, and what do you think are the most important aspects?

“Thou shalt assist the story” – always! It is incredible the amount of work that goes into VFX heavy films these days, but I feel it is important to nevertheless come away thinking about the story and the characters. It is such a shame when an outstanding level of talent is employed for a pretty unmemorable film. VFX is often a real “wow factor” in a film, but you can’t depend on it. Audiences like stories and get used to everything else quickly. Another very important aspect for me is that it’s important to push yourself beyond the comfort zone of the last thing you did. The new level you reach should become the platform upon which you stand to reach for the next.

In terms of roles and disciplines, there are many aspects of VFX that I couldn’t cover in one sitting. However I can talk about compositing from the perspective of an independent artist, and compare this to my understanding of working in a big studio. Compositing is the process of combining multiple visual elements together to create a final image. VFX Games - The Art of Compositing, is a very helpful and entertaining video for explaining the process to others. The easiest way to think about it is keying out a green screen so you are just left with the subject, for which you are then creating a new background.

Becoming a compositor requires quite a long journey. In the studio environment one normally starts as a roto artist, where you learn the process of drawing around things in a shot, frame by frame, so that another background or something else can be inserted behind them. This usually happens where no green/blue screen has been used. It might sound boring, but you learn a great deal of what you need to become a successful compositor, such as the nature of motion blur, how to track movement, how to paint things out, how to optimise and prioritise. When you do this successfully you are also earning the trust of those working at the next level. Eventually you will find yourself working on the final products of a lot of people’s work, namely when there’s CGI involved. The DP, VFX producer, concept and pre-viz artists, matte painters, model makers, animators, riggers, lighters, texturers etc. By this point you will have learned everything you need to know about compositing fundamentals before you even gain that role.

I have been quite self-directed in my journey so far along this road, and learned all the stages of compositing pipeline, depending on the problem I’ve had to solve. I quite enjoy the “invisible” work on shots where no-one would guess anything had been done, and wouldn’t mind focusing on that for a few years.

Independent working can have its ups and downs and working through the different disciplines that need to be learned can be quite a fragmented process. Since you are not constantly repeating the same task there’s not so much muscle memory to rely on. You also have to be resourceful and proactive to learn new tricks with no colleague or supervisor to point out how to do something better or faster. The plus side of this however is that you learn to speak the language of the entire pipeline. Since you are problem solving at every level, this becomes a way of life, so that when you do end up working with other people you find yourself effectively equipped to communicate across all the stages of the VFX process. The other great thing is that you get to work alongside directors, albeit sometimes remotely. The documentary Life After Pi is very useful for some insight into the flipside of this, as it explains not only a director’s lack of presence during post-production, but also an unwillingness for a director to even acknowledge the artists who made their film possible. It also demonstrates how badly people who have devoted their lives to perfecting this pivotal craft can be treated in the industry. Also how far removed VFX artists can be from what is supposed to be a collaborative effort. It made me wonder “Where is the pride, glory and respect in that?”

Do you think of VFX as being more of an art or a science?

I really think it is a balance of both, and people might differ on what creates that balance. As a compositor I would say science is the dominant force, especially computer science. You need to know how pixels work, how cameras, lenses and light works. Bearing in mind that you are generally working on a plate that belongs to a DP, you don’t want to be messing with that plate. You could end up affecting the grade too, so an understanding of colour spaces is important as well as some knowledge of how to handle the way that the shot comes in and goes out. I appreciate the artistic value in any image, but I am glad to be dealing with science. It’s either right or wrong, whereas art can get wishy washy quickly! As long as the brain is convinced by what it’s looking at, the artistic side can be explored between those margins!

What’s the best VFX work you’ve seen in the past year, in your opinion?

Sometimes this can depend on circumstances. For example, I can see why Ex-Machina won the Oscar for visual effects last year when it was up against The Force Awakens! Considering the budget, it is clear that people bent over backwards to make it happen. It was superbly done and integrated seamlessly, rather than being a focal point of the film. I imagine the judges were thinking about what level of innovation they would expect from Star Wars which had a budget of about £250 million, compared to Ex-Machina at about £10 million. Maybe they felt the latter delivered more for what it had to work with.

With that in mind I was blown away by Leviathan, a proof of concept trailer made by Ruairi Robinson, which is another example of an achievement by someone who really knows their stuff. It would be great to work on that if it is green lit. I also rate Hasraf Dulull’s work. He is another entrepreneur who has achieved a lot by himself. I saw his presentation at the VFX Festival last year. It was a self-funded, great looking, proof of concept that won him a bid for a feature film.

When it comes to blockbusters however, my choice would be Dawn of The Planet of The Apes. The battle that Koba leads is a brilliant work of art. I especially loved the shot with the camera fixed to the tank gun, coupled with the shots showing looks of shock amongst the clan as the light from warfare flickers on their fear-ridden faces. It was a great way to convey how they, and the audience, become aware that Koba is nothing like the rest of them, to say the least. Some of the artists at WETA who do the shaders, lighting and compositing are top of the game, although I’m not technical enough to defend that statement in a room full of disgruntled CG artists.

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned in your career thus far?

Work as hard as you can! But try to make sure it is always fruitful. Life is short, you can either end up regretting you didn’t do enough with it, or that you wasted too much of it working. However if that work is what you would do anyway without getting paid for it then you are probably doing the right work! Mica Levi once said to me “If I had to choose between music and people, I’d probably choose music”. I never asked her how serious she was, but it always made me laugh that she contemplated it. She just got nominated for an Oscar on her second ever film score! And she’s younger than me! So I guess there’s something to that level of obsession.

I’ve learned that it’s good to surround yourself with people who understand what is required to get to that next level. A non-creative person might think you are insane when you spend three days perfecting something that only lasts two seconds. However that same person will probably enjoy it in the context of the final film while they are eating popcorn in the cinema, and criticise it if there was anything wrong. So don’t let anyone put you down for being too devoted!

I’ve learned to be more humble. You don’t learn if you aren’t constantly feeling you could be better. When I look back I was pretty arrogant in my early twenties. I knew a lot but had no idea how little I knew, that was the problem, and I still have so much more to learn. I think it’s healthy to assume your life will always be like that. Humility in your work is also important. Nothing is ever finished; you just need to know when to let it go since it could always be better. You can always learn something about the crafts of the people you work with, however small. Having even the slightest idea of how someone else’s job works serves to give you a more holistic understanding of the role you are playing in the bigger picture, and also helps you to better appreciate and respect what the rest of your team are doing.

What’s next for you?

In terms of productions, I’m eager to finalise and deliver some work for an upcoming documentary Man Made Planet that I’m working on with my team at Arrow Media. It’s a story told largely through NASA satellite imagery. It was commissioned by Channel 4 and is directed by Kenny Scott who I recently discovered directed a great documentary on quantum physics, which is a subject I can’t get enough of. It was one of those moments where you realise you are in the right place and working with the right people. Plus who doesn’t love everything related to NASA?

Once that’s done I’m going back to the drawing board. I’ve been working in TV for almost a year now and it has meant I’m not doing as much film work as I feel I need to. Therefore I am planning a couple of months self-study to learn more about the film pipeline. While doing that I will be assembling a new showreel, specifically showcasing my prep and paint work in film as part of my intention to be doing more regular work in the invisible fixes I spoke of earlier.

After that my plan is to apply to WETA, despite the fact that they are based on the other side of the planet and hope they will take me seriously when I show up with a Wacom, visa and no strings attached!