The MewLab founders dish the production of their LSFF award-winning short.

This month we have two Jammers of the Month - Kim Noce and Shaun Clark, the award-winning animators behind the prolific short film collective, Mew Lab. After meeting at the National Film & Television School and graduating in 2005, Kim and Shaun continued to work together, using the name Mew Lab for their collaborative works.

Since then, the two have created a wide range of animated shorts and worked with a variety of clients, including the BBC and Channel 4. Among their acclaimed works are The Key (2014), which won the Audience Award at the London International Animation Festival, Lady and the Tooth (2012), which won a Jury award at Clermont-Ferrand, and their latest short, The Evening Her Mind Jumped Out of Her Head.

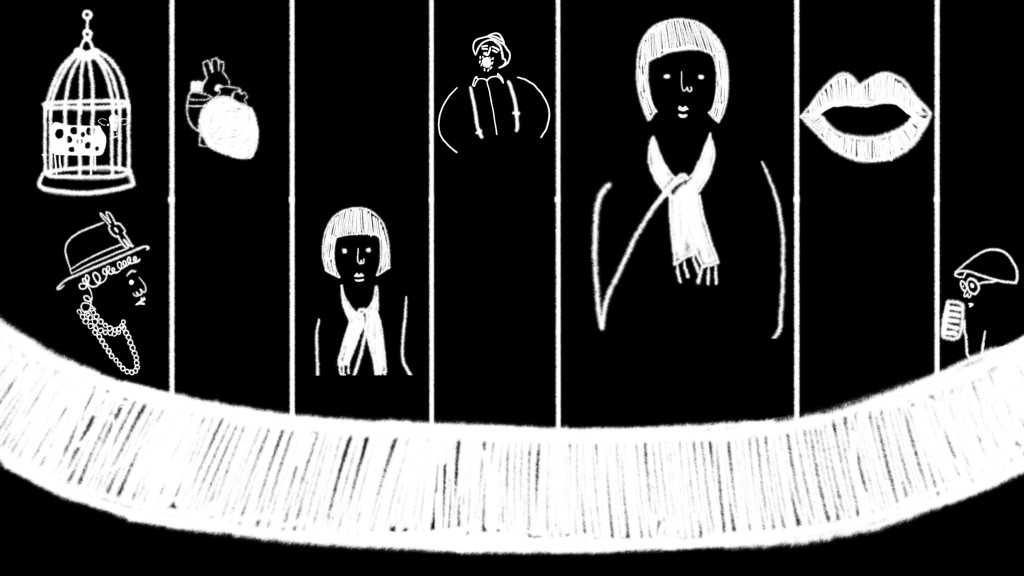

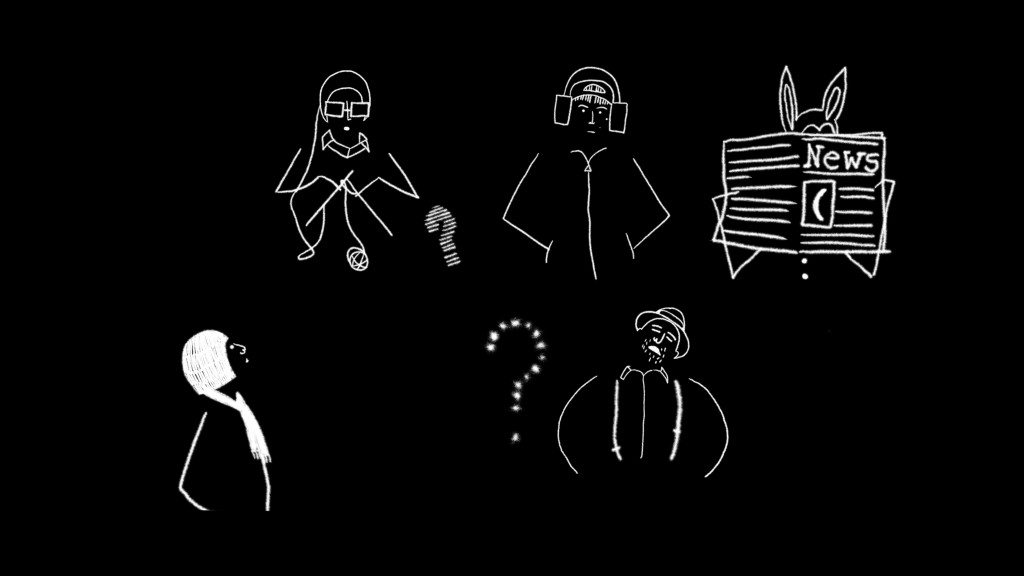

The Evening Her Mind…, directed by Kim and Shaun and written by Sarah Woolner, is an idiosyncratic film in terms of both narrative and animation, combining a unique plot about a woman’s brain jumping out of her head during a train ride with a unique structuring of images into separate sections on the screen. This style stems from the original purpose of the film - a high street projection funded by the Watford Borough Council - though the film has now also worked its way through the festival circuit, culminating with a win for Best Animated Short at the LSFF.

Currently, Kim and Shaun are working on a segment for a feature-length documentary as well as a few other shorts, as always. I caught up with the two to find out more about their work and the process of creating The Evening Her Mind…

It’s been 11 years since your collaboration started - how has it changed?

Shaun: I think it’s got to a point now where we try to mix things up so that each production is slightly different in the way that we approach it. In The Evening Her Mind… we kind of scrapped the storyboard as such, and we did a lot of separate images of parts of the script, so we did a lot of drawings, and we put them all over the floor, and were like “ok, this is the kind of shot we’d like to do here,” and we also built a storyboard between the two of us of the drawings we’ve done, and then we filled the gaps.

So it kept it kinda fresh, instead of always going down the same route, and I think that that is something that we’ll do in out future films, in that we’re always re-evaluating the way that we work, and coming up with new ideas and trying to change things.

Kim: I think one interesting thing is that, when we started, we’d both just graduated and our film was going to festivals, and I think there was a sense that each of us wanted to leave a mark on the film, but as we kind of grew as a kind of collective and we did more work, there was less tension on the film, and more importance on collaborating and merging.

We’re always re-evaluating the way that we work, and coming up with new ideas and trying to change things.”

What was the original inspiration for “The Evening Her Mind…”?

Shaun: we’d gotten a commission from Watford Council to create a building projection on one of the buildings in the high street, so what we wanted to do - it was obviously a family-oriented piece as a celebration of part of an event that was happening at the beginning of 2015, so we invited Sarah [Woolner] along to Watford to have a look at some of the buildings with us, but we were quite keen to allow Sarah free reign in; we wanted her to do what she’s good at, and she’s fantastic at writing stories, and coming up with different ideas, so we asked her to write as many synopses as she could - just one- or two-liners - and to send them through, and we would discuss with her which one was worth developing, and she sent through quite a lot and there’s quite a few really, really interesting potential stories, and the one that we chose was exactly the one that Sarah had at heart.

Kim: yeah, and Sarah is a good reader of what you want, without actually explaining too much. So she came to Watford, sucked up the atmosphere of the place, and without too much telling [came up with the idea]. It’s very rare to have a script writer that is that in tune with animation. A lot of script writers, they’re wonderful, but they’re [more] for live action, and you can really feel it in terms of the dialogue. She can write that moment that can only happen in animation - that sort of transformation that can only be imagined into pictures. I mean try imagining having a brain escaping your head. The effects would be insane in live action.

You say that the film was originally a building projection, can you tell me more about that?

Kim: they commissioned us to build a projection and we wanted to make a narrative, so we kind of took the commissioners aside and said “do you mind if we do a projection, but then actually afterwards we remove it from the building and it’s a standalone film itself?”

So some of the framing is due to the mapping projection - the fact that there are things in different parts [of the screen] - but we actually embraced it. At the beginning, we were a bit picky because we were like “that’s not a format usually used for film,” because there’s some white area where you couldn’t project, where there are windows, so we needed to use some specific area of the screen.

But we decided to absolutely embrace it, and tried to create a narrative where it’s not a specific 9×9 like you would use in photography, but more kind of a block, and if you think about it you can see that each character’s got their own block, and their specific area where you use them and don’t. And we really enjoyed creating a really different type of storyboard and trying to apply the roles of cinematic language to a completely different type of space, which would be kind of split-screen, but a bizarre split-screen, because it’s an [old] building - so everything’s slightly off and it’ll never be a perfect split-screen.

And we kind of really liked that element; sometimes we really feel like if there is a limitation, use it to your advantage, because it will make quite the difference in the work if you embrace it rather than consider it a limitation, and try to push maybe the 16×9 format into something that wouldn’t work.

If there is a limitation, use it to your advantage.”

Did you find that audiences reacted differently to the projection than to the film as a standalone?

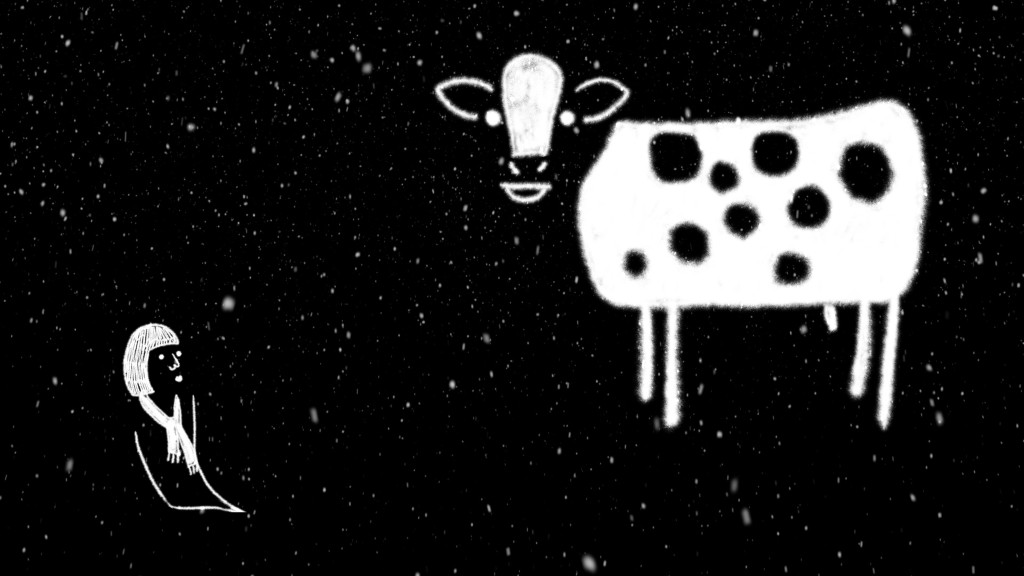

Shaun: yeah, definitely, there was, as you could imagine, this was being projected in January, 6 o’clock to 8 o’clock in the evening, it’s snowing, it’s cold, and people are on their way home, so a lot of people were stopping and staring, glancing twice and thinking “what on earth is going on?” or quite curious about the projection that was going on.

And obviously in the cinema you’ve got a completely different audience, people are sat there expecting, waiting to see a film, whereas in the high street on your way home, you don’t except to see a film projected onto the face of a building.

Have there been different reactions to the film at different festivals?

Kim: It’s funny; each film has gotten different reactions. Some films end up in some countries and some in other countries; we did one film and it ended up that all the Eastern European festivals liked it, and this film is more [popular in] Southern Europe, and Portugal. And you realize the film [taps into] certain tastes or certain trends that you weren’t aware of.

Besides this film, have you experimented with different animation techniques in the past?

Shaun: we’ve used quite a lot. We tend to develop the idea and the story and themes of what we’d like to express, or if we work with a writer we’d look at the script, and we kinda we think “which is the best way to make this film, this story?” and so sometimes we end up making sets out of cardboard, and we’ve done a lot of 2D work, even underneath the camera with paint or rotoscoping, and we’ve also done digital, hand-drawn animation inside the computer, like traditional 2D. The only technique that we don’t tend to do is 3D, CGI, we’ve got a lot of films and a lot of animation based on a lot of the other different techniques, with pixelation and even mixed live action as well.

Is there a specific reason why you don’t do 3D?

Kim: maybe we’re not used to the tools.

Shaun: and sometimes 3D can look incredibly dated, even though it’s modern right-here-right-now and you look at it and go “wow, that is the best, and that is where 3D’s up to right now,” but in three or four years time it can look a bit dated.

Kim: another thing about why we change technique; it’s not willy-nilly, it’s that every film, we feel, requires a different approach. Some stories will rather be a film, or a theatre show, or a dance piece, or whatever. Sometimes we feel like each story requires a different technique, so for example High Above the Sky was in cardboard, because it was a children’s film that was funded by the BFI.

The idea was that everything was gonna be made like something a child could grab and use and paint. And the cardboard box was the most usable narrative, so everything was on that level. And every film has got a slight idea behind that. Forget Me Not, which I did for Channel 4, was all about memories, so it was a collage of photographs from the Brussels museum and my own photographs.

Do you think in general that the animation industry is in a good place right now?

Kim: [laughs] ouch, that’s a difficult one.

Shaun: I’m not sure about whether feature-length animated films are going in the right direction; it seems to be a lot of the feature-length films that are commissioned, there aren’t many risks taken, and they’re very, not mundane, but they fit into niche boxes, because all of a sudden you have to please so many different people, so I think in that case it’s a very tricky one.

Kim: I don’t mind [mainstream children’s animation], but it should be balanced by good independent features, which, you don’t really complain about this sort of thing for live action - there are children’s [films] for live action, there’s this whole range of films, but there isn’t in animation, you just get the ones for children, and very few ones by filmmakers who risk eight years of their lives to make a feature and lose all their money…less diversity. But I think there are a lot of potential feature-length animation directors out there who don’t get the chance because there aren’t the funds.

Finally, what advice would you give prospective animators?

Kim: God, just one? Probably to put yourself out there, constantly. Animators tend to work a lot by themselves, but now you have to market yourself. You really have to put your work out there, and carry on working, because it will take a bit of time. It’s different with most animators, who will usually work for a director, but with director-animators, who are trying to get their own stories out there, it takes a bit longer, the role is slightly different.

Shaun: keep animating, and look at different ways you can animate. I think a lot of animators tend to get meticulously bogged-down in trying to recreate what we perceive to be real life, and it’s almost what you would see in live action films, which is beautiful and a skill in itself, but I find it quite interesting when animation goes beyond trying to recreate what we visually see ourselves with our own eyes.

Find outmode about Kim and Shaun’s work at mewlab.com.