John Higgins sits down with an icon of British cinema to discuss a career spanning almost 50 years.

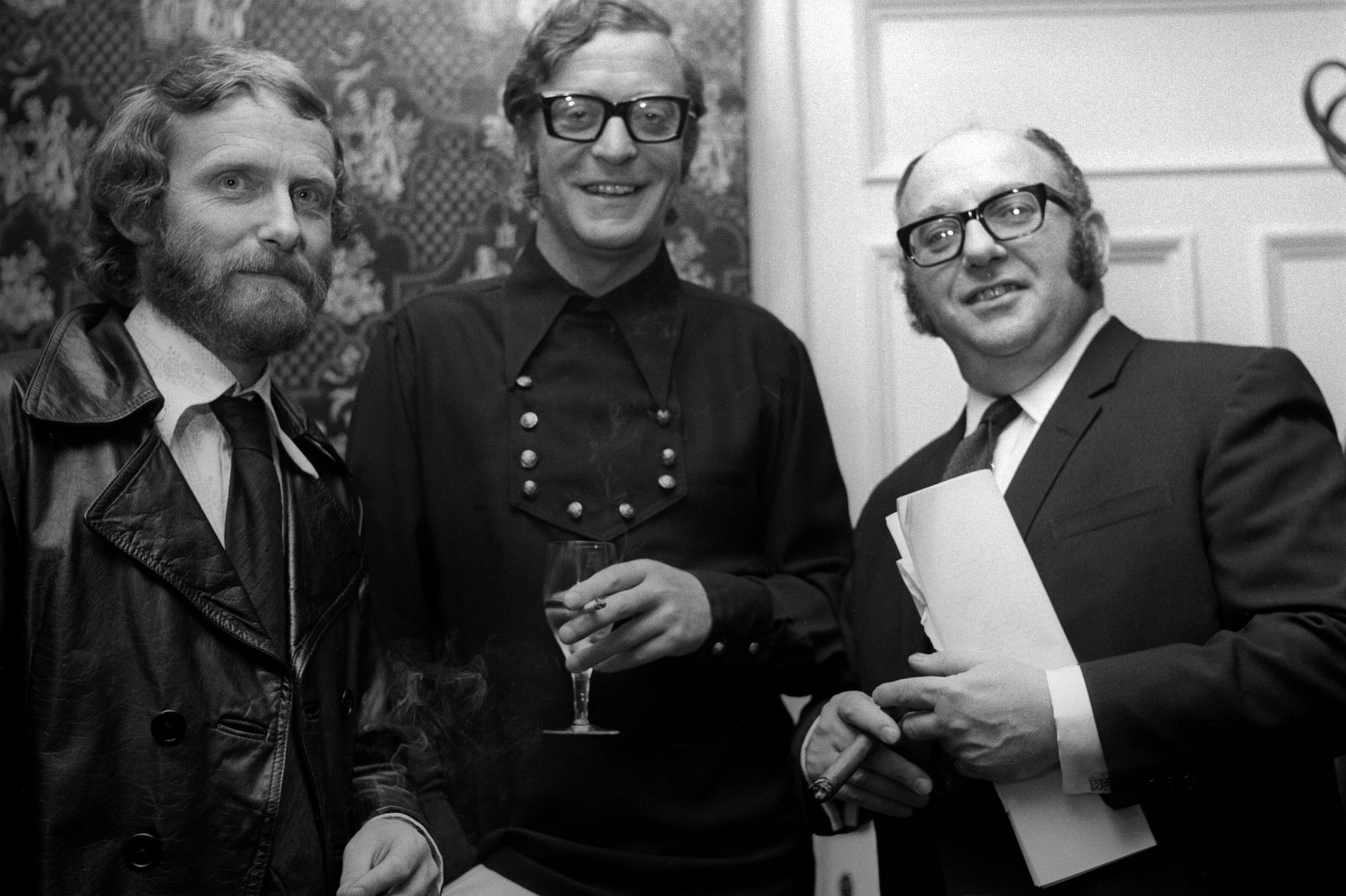

If there was ever a key figure in the UK Film Industry that personifies true independence and entrepreneurship, it is Michael Klinger. The late producer was the driving force behind what many regard as the greatest British Gangster film of all time, Get Carter, which continued Michael Caine’s career to great success.

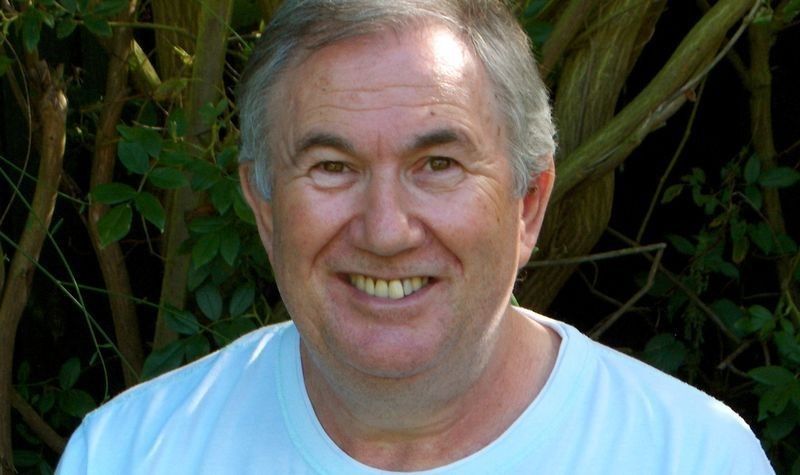

I had the pleasure of interviewing his son, Tony, over coffee to discuss his father’s career and his own, in a career that has spawned half a century, not only working with his father, but on classic TV series like The Avengers in the 1960s and films of his own up to the present day.

Given your father Michael Klinger’s pedigree in the Film Industry during his career, how challenging was it for you to make your own mark in the world?

They are two separate things. I chose to go into the business when he wasn’t in it at the tender age of eight. We moved wherever his work took us. Hackney to West Acton to the Isle of Wight and Stoke Newington to Stanmore and eventually Mayfair, wherever the business went. We all had something to do and I was sometimes put in charge of an Ice-Cream stand when I was two or three years old. My father said to me that when customers come, give them an ice cream, put your hand out and take their money. It was a different world, as far as I know no one ripped us off!

My father was an engineer before, during and after the Second World War. I only found out through his obituary that he’d volunteered 11 times to join up with the armed forces but he was in a reserved occupation which meant the government authorities effectively drafted him and people like him, who they considered essential, to remain in their jobs. He told me he hadn’t been a hero but was desperate to get out of his reserved occupation. They kept him in that factory between the late 1930’s and about 1952. He didn’t have any money and he was very frustrated. He was desperate to make a living. I think at one point he was running a munitions factory with two thousand workers for just a few pounds a week.

But dad was a very clever man. He saw opportunities wherever they existed. His parents’ in-law ran what they laughingly called a factory but was actually a sweatshop. Involved in cutting cloth for the coats is a process called cabbage, which allowed the legitimate manufacture of extra coats for the manufacturer of the coats he is making for the retailers. His brother in law was a master cutter and they were making children’s duffle coats for a High Street chain and the cabbage allowed them some coats of their own to sell in Shepherd’s Bush Market. Sometimes I modelled these coats when I joined him at the market. My father was very good at sales even then. I was set up to walk near to his stall with one of the duffel coats on; he would ask ‘Does that coat feel good on you?’ I would respond, “It feels lovely.” However, I never could resist the chance to add ‘Dad’ (laughs)

My father was also responsible in the creation of one of the first domestic toasters after the war. Given his engineer background, he would subcontract parts to various manufacturers, who simply didn’t have the skills he was used to from his days in the armaments factory making munitions. Our flat in Hackney and our maisonette in West Acton were like a workshop at times. When we moved to Stanmore, I went to school in nearby Edgware and my school entered me and the rest of my classmates into writing competitions sponsored by Cadburys and Nestle based on films they showed us about how chocolate is made. I won one first prize and shared another.

The reward was basically as much chocolate as I could eat and this being announced in front of everyone plus a highly desirable and then very exclusive visit to the chocolate factory. That’s how, in my kid head my career really started and ever since then I have been writing in search of chocolate. Writing, filming and then eating chocolate! Just substitute some cash for the chocolate. It took me many years to figure that out. I had an agent at seventeen or eighteen and got an offer of £2,500 to write my first book, which I turned down. Then it took me about 40 years before I wrote my first book and get it published.

My father built his first cinema, the Compton Cinema Club, to be created after the war and that was in the early 60’s. It was a huge success and then he either bought or built many more within a very short period. In just a year or two he had developed a chain and within another year or two he also created the biggest independent distribution company in Europe. But with cinemas and a distribution company you need films or you’ve just got a machine with no oil. As a result he had to guarantee a steady supply of films that were unique to his organisation and the first of these films was Naked As Nature Intended (the famous naturist film by Harrison Marks).

He learned to be a producer on the job and it was this and the many productions of a huge variety of films that culminated in Repulsion and Cul-de-Sac with director Roman Polanski that, as a result gave him the launch pad to become a fantastic international producer, probably the most successful in the country for about fifteen years. My dad and I came into film making from opposite ends and for years there was a general lack of respect for each other. I’d come from the floor of film sets and knew all the technical grades whereas he’d learned the industry totally from the other end. It was only when someone suggested we work together and as a result gained a lot of respect.

The recent death of veteran Wild Geese producer Euan Lloyd has signalled the end of an era for that type of entrepreneurial approach to filmmaking in the UK, something that your father was renowned for. How much has the industry changed in terms of securing the kind of deal that got a film like Get Carter made?

Get Carter still could happen today. It was a medium budget film for its’ day and decisions like that could still be made by a brave executive like Bobby Litman who was then the newly appointed head of MGM Europe and we were lucky to know from his time as an agent. The timeline is impressive. From the day we first had the book, Jack’s Return Home by Ted Lewis in galleys to when the film was first released in cinemas was a total of 37 weeks. It was a classic case of the stars aligning and the perfect storm.

Get Carter still could happen today. It was a medium budget film for its’ day and decisions like that could still be made by a brave executive like Bobby Litman who was then the newly appointed head of MGM Europe and we were lucky to know from his time as an agent. The timeline is impressive. From the day we first had the book, Jack’s Return Home by Ted Lewis in galleys to when the film was first released in cinemas was a total of 37 weeks. It was a classic case of the stars aligning and the perfect storm.

The flat you see in the opening shot in Get Carter was found through a girl I was dating who knew a British gangster who owned the place and was OK with our using it to film in. Euan Lloyd was not the same type of man as my father. That’s not meant to be a critique of Euan but if you read Andrew Spicer’s fine book about dad, The Man Who Got Carter, you’d soon discover their many differences. Michael Klinger was the best Script Editor and Producer and had a tremendous ability to sell. Producers today have become more supplicant in their approach and there were only a handful in my father’s day that had that gift, even less today. It’s no accident that my father made so many fine films when he was left to his own devices. He also could pick talent and nurture it. People financing films today tend to think in terms of the tax deals and soft money being the key to making a film, but here’s a thought:

If you flattened the world out and based it on incentives, the Russians and the Chinese got money on a plate, which is why the Chinese only ever thought in terms of domestic releases. The UK and Europe got some money largely as a cultural imperative or to employ their local technical and film making talent whereas the USA producers got no money. The irony is that the results were in direct opposition to these supporting funds because the Americans prospered the most while the Chinese and Russian films simply didn’t find an audience outside their own territories. Market forces dictate taste and results. Many young producers are following their craft for the wrong reasons and it is all top down wrong and bottom up wrong. The key question is to make what people want not only what you want to make. You shouldn’t go into production to earn development fees; the rationale is all wrong. People should think it through and as a long-term strategic investment and not as a short-term bit of fun.

The once mighty Rank Organisation had the money back in the day and we could have bought into the distribution ideal, but didn’t and as such our country have become an outdoor workshop making wonderful films for the US based on our incentives being used for their benefit and that’s largely insanity on our part. We haven’t had the money because we don’t have the film industry, because we never invested in the American distribution super powers also known as the Majors. No they make their films here because it suits then, our people get wages or fees but the ownership and the big income goes straight back to the USA.

Get Carter is the yardstick by which all subsequent British Gangster films are compared. Why do you think it has endured today?

Attitude. My old man came from Soho, which was a tough area at the time he was growing up in the 1920s. It was effectively a Jewish village, next to an Italian village next to an Irish village, much like New York. Some people said that it would be fine in one area, but if you tried crossing the street to the next area and you would have to fight. My father encountered a lot of gangsters between engineering and Film and at one point, when he ran a nightclub, some gangsters came along demanding protection, but he chased them away. Real gangsters don’t threaten, they just do. When I worked as a projectionist at fifteen, I was being threatened, but this one gangster came up to the guy doing it, whispered something in his ear and the guy’s face turned pale and the trouble stopped. Scorsese has that attitude in Goodfellas and it’s that attitude that has come across in Get Carter. It had never been covered in British Cinema up to that point, although there were examples like Brighton Rock that covered similar ground. Get Carter also touched on Child Pornography and other pornography.

It was shot in Newcastle and I was up there for two weeks. Part of the appeal was Newcastle and how it was, that was exciting and kind of untamed and very different from London. I had the best time while filming our own locations for our documentary, Extremes. But being close to the filming of Get Carter confirmed me as a huge admirer of Michael Caine and a firm fan and friend of director Mike Hodges. When it was first screened on BBC they cut it telling us they were doing the filmmakers a favour. The attitude was the big mistake with the Stallone remake, because that film was about redemption, which is the complete opposite to what the original film was. An interesting footnote to the film is that in the climactic scene, there is a ship in the background. Somebody actually tracked that ship afterwards, it’s entire history right up to four decades later when it was demolished for scrap. That’s what the word fan really means!

You mentioned to me ahead of this interview that your documentary The Man Who Got Carter was 75% completed. How have other members of the family and filmmaking community reacted to it and what can fans and film enthusiasts expect from it?

It started out as a straightforward documentary. I regard myself as a writer and documentary filmmaker. What transpired was that there was only a tiny bit of real archive footage of my father, merely some audio visual and it became apparent that I would have to create a feature within a documentary.

We are aiming to use VFX to represent and recreate Soho as it was. The bit that would make it even more interesting and what I want to get across is my father’s humour and ability to be able to tell a story. When he was in the USA one time, he swapped jokes with comic legends like Red Skelton and Rodney Dangerfield and they said that he should have been a comedian. The other 25% is to do with casting. At one point it was suggested that I play Michael Klinger, but although I look like him, he was shorter and plumper. I am looking to cast a name actor in the guise, and whoever it is will most likely be a better actor than me!

Your father’s filmography provides an interesting contrast with films like the Confessions series, Repulsion and Cul De Sac all forming part of the overall picture. I also note Naked As Nature Intended, the famed Harrison Marks naturism documentary amongst the titles. Today filmmakers are lucky if they get one or two films out a year. Are developing talents making the same kind of mistakes as they were back in the days of your father producing?

It’s about the cinemas enabling the cash flow. My father was misunderstood because of his Cockney accent, but he was a very cultured individual. The story about Confessions is interesting. When I was about to go up to visit the set of Get Carter, my father recommended I read the source material upon which that film was eventually based. He said that if I line produced it, he would be executive producer. I wasn’t that keen on the book, so turned it down. Later, when it became successful, it transpired that Columbia had to pay tax on the film in the UK because it was so successful. My father told me that if you want to make the quality films, the success of a film like Confessions enables you to do that.

A Study In Terror is another example of how to put that kind of film together. The reason why Confessions Of A Window Cleaner worked is because people like to laugh at sex, not just sex for its’ own sake but because he saw nothing wrong with people laughing or looking at beautiful naked women. He also remembered that his first film, Naked As Nature Intended played in London’s West End for more than a year and a half.

You have been involved in the education side of film-making, lecturing and so on and it is something that you have intended to bring out with the advent of social media and the internet, with several projects you have mentioned in preparation for this interview. How has your practical and emotional experience aided those aspiring to be where you and your father were in the film world?

I try and do as much as I can. After a variety of roles while I was living in the States I was offered the role of Head of Production with a company called Marquee Entertainment. I was disenchanted with the business at the time and although I was offered a terrific deal to start work with them, but had an argument over who would actually control major productions being green lit. My new employers wanted it to be the Board and I wanted it to be me within agreed parameters. We couldn’t agree so I never took up the job offer or the lovely house in the Pacific Palisades or the brown Beamer and we left the USA.

Unbeknownst to me, my wife had applied on my behalf for me to teach Film at the Bournemouth Film School. I had never previously been interviewed for a job and ended up interviewing them. I got the job and the excitement and pleasure of my students reignited my passion. I was lucky enough to get promoted several times, to the point I was Director of three different Departments at the University of East London after previously being Course Director of various undergraduate, degree and post graduate film production courses at the Northern and Bournemouth Film Schools. As a result, I got the desire to make films again and that got me back in it.

Unfortunately, academia has a lot of misunderstanding when it comes to the sharing of knowledge and that is why I put together Give Get Go, an new initiative whereby it gives people a chance to create creativity without the bureaucracy. If I share knowledge with you we’ve now both got that knowledge, I didn’t lose anything by sharing. I just want to release and share creativity with everyone.

Next to Love, I believe the most desirable word in the English language is creativity. Everyone has creative ability, but perhaps they don’t know the way forward or the path to get to that moment of revelation. I thought that if we could create a cockpit with a table of two creatives from every major creative discipline, who have the only guarantee that they must help each other. Sharing an idea, generating ideas, saying and doing it. Then, you go and sell it. If I can inspire others to create an opportunity for others, we can make people into something creative.

Give-Get-Go creates the framework in which we can create the cash flow to enable us to self-fund that dream allowing everyone to be creative. Here’s the primary difference between UK and US films – the UK look inward and down, the US look up and outwards. They look for universal themes we tend to want to make stories where two blokes are talking in a pub. Yet when we make films with American money we are more than capable of making huge very commercial movies but all the money goes back to the States

You worked on Rock Film projects with the likes of Deep Purple and notably The Who with The Kids Are Alright Thinking back to the latter film, it does capture in some of the segues the essence of what The Who represented to the music world and their fans, particularly in some of the antics Keith Moon gets up to during one or two interviews. What would you say is the key to capturing a band’s heart when you make a film, given that music and film although relative is totally different in feel and context?

Understanding the people. I was more interested in the three people that hired me (Keith Moon, John Entwistle and Roger Daltrey) than the one that didn’t. What we tried to do with Keith Moon was capture that lightning in a bottle. We saw the film as a rockumentary, like The Marx Brothers mixed with a Rock film. The performances at Shepperton (including Won’t Get Fooled Again) were the first time The Who had played together in two years. One promoter said to me ‘I could get £2 million for them to play at Wembley and here they are playing in a soundstage’ Because I knew Keith was not going to last (Moon died on September 7th, 1978, after a screening of The Buddy Holly Story, as a guest of Paul McCartney) we switched the schedule so we could capture the energy and power of his performances. At one point, he consumed £30k of blow in a week and one of his favourite phrases to me was ‘You can’t afford the truth!’. Beneath the madness, Keith was a very personable guy. The production was fraught with difficulties and you had to be on your guard.

You published a book about the making of The Kids Are Alright, called Twilight Of The Gods, in 2009 How has the tie-in world changed with the advent of the internet and so on?

Just A Boy, my upcoming production has a tie-in in 150 countries by Forever Products and we will be promoting tie-ins through social media. It is so essential today in the marketing of anything. My old film Extremes is being marketed through the BFI. You need to have the want and the desire to get people to see your work. On Twitter for example, I have 30,000 followers. Now, it is not something I have normally done, but it gives me the help to get something going. What is the brand? Is it the product of the person who makes the brand?

You began your career as an Assistant Director on The Avengers TV series, which is iconic and fondly remembered for Patrick Macnee and the chemistry he had with the likes of Diana Rigg and Linda Thorson. Much has been written, but what would you say are your key memories of shooting and working on that show and although we have had the Ralph Fiennes / Uma Thurman movie, do you think a reboot would and should work in today’s market?

I know I was working on the best and biggest budget show in the world. We were an American show and often ABC executives would come over. The directors on the show were either the greatest coming up like rockets or the veterans on a gentle slope down. People like Peter Yates, Charles Crichton, John Hough, Don Chaffey and Leslie Norman.

My partner, Mike Lytton and I used to borrow equipment from series we were working on at the weekends, well borrow without asking but returning it all in one piece before anyone noticed. I was on The Avengers and he was on Department S or Randall & Hopkirk (Deceased). Without thinking about it we created the best film school in the world. On The Avengers we sometimes had five units shooting to keep up with the broadcast scheduling requirements out of New York. So when someone on staff fell ill, you’d be told to take their place and you either learned what to do really fast or someone would take your slot and you went back down the ranks. It was an incredible experience.

Suddenly from being a third assistant director I could do the odd day as a camera assistant or help out with the sound department which proved invaluable for me later as a film maker. And at nights and weekends, whenever no one was around we would be taking cameras out of the studio and shooting our own tiny films and editing them overnight in the studio cutting rooms. I don’t think anyone ever found out or maybe people just turned a blind eye to our nocturnal activities!

What were the actors like on set and did you have a particularly favourite episode from The Avengers?

I didn’t have a favourite episode, but there was a tiny scrap of an action scene I got to direct which they scrapped as soon as they realised I’d done it. Where London was deserted and I had to stop traffic in London for a whole day! A proud moment and one that definitely took chutzpah. My favourite memory of Patrick Macnee and Linda Thorson came after an awkward moment when I went off to Prague for a location reconnaissance trip for a new film for my father. I was due two weeks holiday but needed three weeks for the trip to Czechoslovakia so I was allowed the period but as leave without pay. Well everyone knows that the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia while I was there. A little too exciting a trip as we saw the tanks roll in and the film dad was due to make roll away. I came back and was told that I had in fact resigned from the production and wasn’t needed. The producer was clearly jealous of my father and for reasons of his own pretended we didn’t have an agreement for me to have the unpaid leave. I told the union who did nothing so I was going to lose my job. When I told Patrick, he and Linda took me to lunch and said he wouldn’t go back to work until I was re-hired. The producer suddenly remembered our original agreement and took me back but Patrick insisted they not only re-hire me, but also give me a raise, which they did!!

You were Line Producer on Shout At The Devil, with Roger Moore and Lee Marvin. What are your memories of working with Mr. Marvin?

Lee Marvin was a hell of a professional and a hell of a man. He worked with total professionalism and all his normal brilliant skill. He did get drunk one time in the four months he was on the set, but that was a day when he wasn’t working. He was a true star and always effortlessly outdid Roger. A case in point. Roger flicked a cigar up and caught it in his hand. Lee took a soft pack of Marlborough cigarettes, banged them on a table. One cigarette flew out of the packet, circled twice in the air and ended up in his mouth!

Back in the 1960s you worked on specialised films for the Ministry of Defence. It recalls an era when a lot of top directors, particularly those during the Second World War in service, cut their teeth on doing that type of filmmaking to the extent that it shaped their creative mindset when they wanted to tell a story. How did working like that influence your personality as a creative?

When you did that work which was covered by the Official Secrets Act. They intentionally kept the crew to the essential few people it took. This would normally be about 1-2 people, so whether you were recording nuclear bombers refuelling in flight or fighter planes, minesweepers or submarines on exercises or missile tests, it would be full hands-on doing all kinds of things, filming, editing etc., relaying it back to the MOD. You had to be self-sufficient in a number of things and therefore gained a good general knowledge. It certainly put me in good stead because at one time I was on a minesweeper during terrible weather, we lost a camera overboard and everyone, including me was seasick but, although I was just 17 we was in charge and you learned fast that you had to be comfortable in your environment. I then worked on ATV’s Junior Sportsweek and ended up, although just an assistant interviewing people like Bill Shankly, Liverpool’s legendary manager, prior to a huge derby game between Everton and Liverpool. Again you learn fast in circumstances like that.

The main upcoming feature film project for you is Just A Boy, which you have written the screenplay and producing from Richard McCann’s novel. Researching it recently tells that it has been in the works for a decade according to Richard’s online announcements. What attracted you to the project and where do you think it will fit in in the grand picture of film releases?

We have been working on this for two years. We filmed the opening and closing sequence at a huge event in Liverpool’s Echo Arena. We are casting the stars and crewing up in the next few months, with a view to filming in Leeds next Spring. My initial reaction to the book was not to touch it, but after meeting Richard I found his story an inspiring tale of redemption. In that respect it is the complete opposite to the equally wonderful Get Carter. Richard has presented at over 2,000 events in the last decade. It is a compelling story of triumph over adversity. He embodies everything and he has been through so much. Of course, its natural Richard continues to be haunted by his mother’s death, drugs, imprisonment and so on but ultimately it is a celebration of his truly incredible triumph over terrible adversity. I see it as a story best told with that uniquely dark British Humour. When I was at Northern Film School I used to drive past Richard’s childhood home without knowing we would be working together one day.

Just A Boy has elements of the fish out of water type stories found in Crocodile Dundee and Midnight Cowboy. To get that fresh look at this type of subject I am looking to engage with an American director who can bring a different perspective to it, like John Schlesinger did the other way around with Midnight Cowboy.

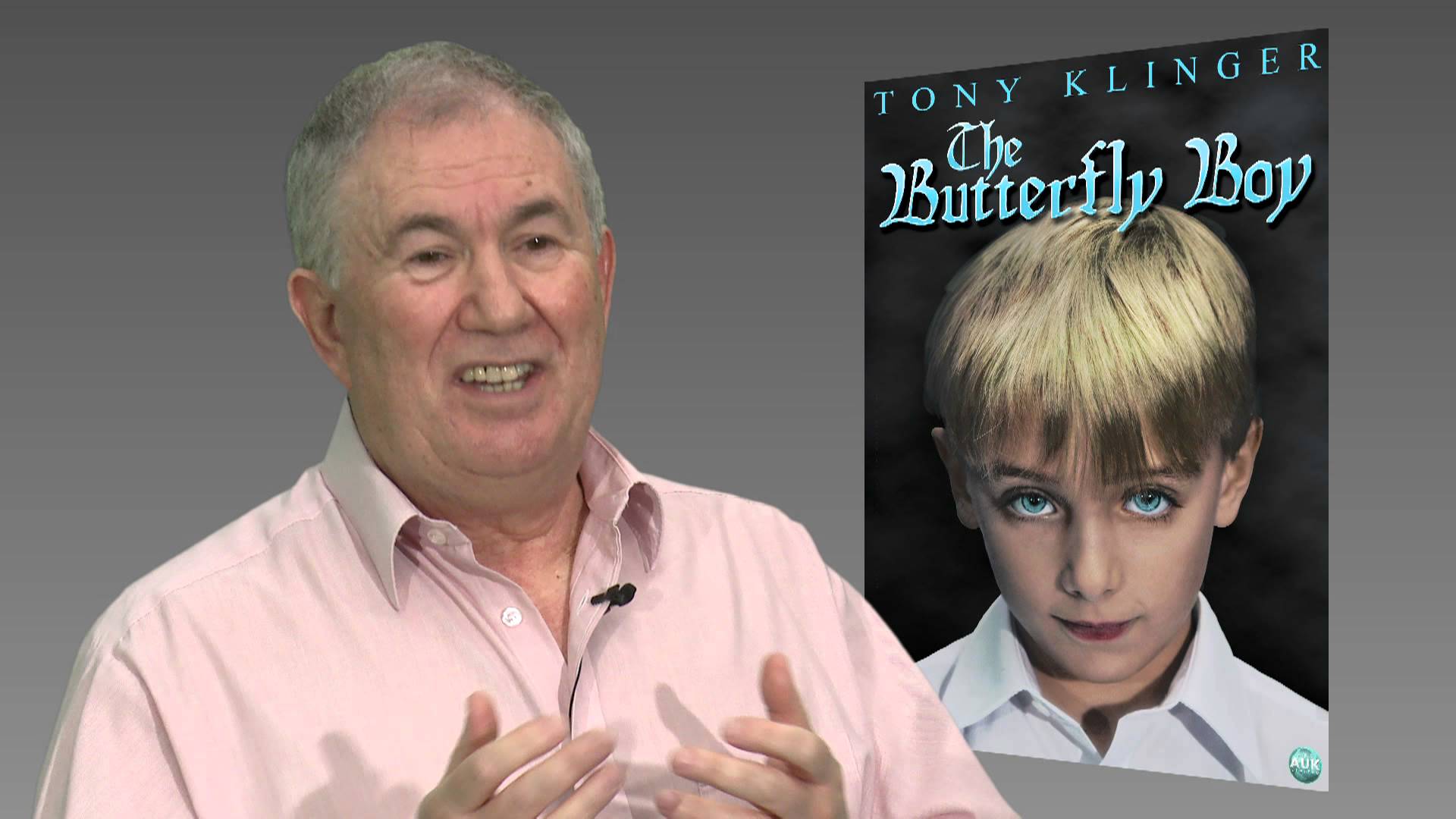

Let’s talk about your books Under God’s Table and The Butterfly Boy. Are there plans to adapt them for Film or TV?

Butterfly Boy has been adapted into a four-part mini-series and it will work well as a TV piece, but we haven’t yet started to pitch it to networks either in the USA or UK. Under God’s Table and I haven’t really found the right way to publish it yet but when I do we will also be looking at it as a potential major feature film. Wait until you read it and you’ll soon see why.

Finally, Looking back at your career, which would you say is the proudest moment so far? Obviously you are still keen to carry on, but if you stopped now and took a step back, what would be the thing that defines you as a person and a creative?

Firstly comes my family. Secondly, I’d also be hugely proud of the fact that I created something of ongoing value. If you have done something in your life that resonates down the years, you are not merely the richest person in the graveyard; you’ve achieved something very worthwhile. If I can be remembered as a person who communicated interesting and worthwhile ideas, then that’s what counts.