We look at how the already-infamous flop of Tom Cruise’s The Mummy can teach you everything you need to know about where Hollywood is heading.

The Mummy has a lot of bad reviews, I wrote one of them, and it squats in that awkward position, when analysed statistically, because it was just enough of a success in the global market to turn a slight profit but nowhere near close enough to the realm of true blockbuster success. The kind of financial success which absolves all failures of judgement.

The film, itself, is mostly of note because of its most damning failure, both in a creative and financial sense. (The Mummy was intended to be the first in a series of interconnected films released by Universal Pictures, each of which being a remake of a classic Universal horror property.)

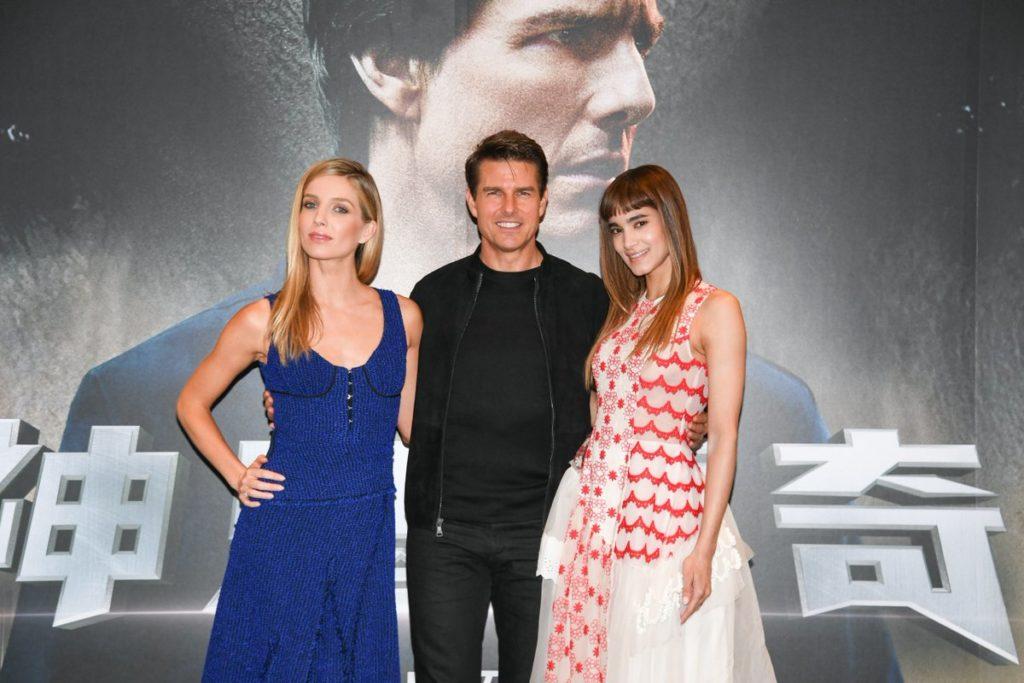

In a moderately stunning act of hubris, the producers of this so-called Dark Universe (key founding producers Alex Kurtzman and Chris Morgan have since resigned from the project and the production offices on Univeral’s lot have reportedly been vacant since late last year) released a cast photograph before the release of The Mummy which featured only three cast members of the film (Sofia Boutella, Russell Crowe and Tom Cruise) alongside two other famous actors (Javier Bardem and Johnny Depp) who were not in the film. The implication being that these actors were to star in other films of this same cinematic universe which had not yet begun production. (Crowe’s character serves entirely as a bridge into these films.)

It wasn’t so much that Universal Pictures had already attempted to kickstart this very same endeavour three years previously, with the more modest disappointment Dracula Untold, it was, rather, the strident confidence of The Mummy that really makes it shine as an example of modern Hollywood’s entire thought process.

Crowe’s inclusion as both Henry Jekyll and Edward Hyde in this, a reboot of Stephen Sommers’ action adventure trilogy which spawned four spin-off films (the first of which launched the career of the, currently, highest paid actor in Hollywood with a fifth coming this year) which was another reboot of a property so iconic that they even made an Abbott and Costello one, is not just unnecessary to the story but a definitive decision.

Connections to the proposed Dark Universe in Dracula Untold came about as a result of reshoots made after principal photography had already wrapped. Though cliched and hammy, it was a film which existed for its own sake. The Mummy hinges its entire identity upon accomplishing one goal, which it fails to do. (The next film in the franchise, Bill Condon’s Bride of Frankenstein remake, has been put on an indefinite hold.)

The worrying thing is that this isn’t an uncommon practice. The Mummy owes its existence to the success of one Universal Pictures film in particular and that film is not Karl Freund’s 1932 original starring Boris Karloff. (One of the purest of all Univeral’s original monster hits, not being directly adapted from a specific literary source unlike Frankenstein, The Invisible Man or Dracula.) The Mummy exists because of Jurassic World.

It’s depressing enough when you realise that the idea was most likely initially pitched as a Chris Pratt vehicle. (Aside from the rugged adventurer vibe, that would fit with Pratt’s developed star persona as a man in perpetual contention to be a rebooted Indiana Jones, the inclusion of Jake Johnson in a comic relief supporting role echoes Jurassic World, strongly.) But the soulless formula of it all is achingly apparent. From the implied sexual activity that happens off-screen before the film’s story even begins to the, noticeably heavy, use of exposition and inoffensively generic slapstick - The Mummy is not a film that was designed to please audience members. It was designed to please censorship boards.

As numerous people have pointed out in the wake of the film’s release, a more logical approach would have been to produce the films in a similar way to Jason Blum’s Blumhouse Productions model. (Granting filmmakers more creative control in return for a significantly reduced budget, often resulting in sizable profits.) And this is, apparently, the direction that Universal now want to move in going forward. The problem, from Universal’s perspective at least, would have been that, while profitable, low-cost/high-concept films make most of their money domestically. And the real holy money grail of modern day American filmmaking isn’t America. It’s China.

It’s easy to see why that’s the case. In 2015 alone, China was building, on average, twenty-two new cinemas every single day. That level of investment in just infrastructure alone lead people to believe that China’s box office takings could eclipse the North American market within a matter of a few years from that point and, with three of the five highest grossing films of the first quarter of 2018 being Chinese, it looks like it’s an accurate assessment. Aside from drawing attention to how number obsessed the film industry at large has become, it’s something that’s got a lot of people shifting in their seats, both at home and in cinemas, for a plethora of good reasons which The Mummy serves to highlight.

As writer and director Wong Chun-chun put it: to appease China’s stringent censorship rules “you must make movies that a five-year-old can watch without feeling scared.” Which isn’t a great mission statement when you’re making a horror film. Roger Garcia, executive director of the Hong Kong film festival, stated a few years ago: “In China, you are making either a romance or a big special-effects movie. If you want to do horror, or other genres, you cannot be in China.” And if that isn’t an unequivocal statement on the matter then I don’t know what is.

Of course, Garcia was mostly referring to productions in Hong Kong that wanted Chinese releases, or financing, but his warning for Hollywood was perhaps more ominous: “You can make a budget sci-fi movie in Hollywood, but Chinese audiences will not like that. They like huge, costly productions. So I think that China should not be the total sum of everything, it is a mistake. It is limiting. For Hong Kong, it was a mistake to obsess about China. And things are changing now that Hollywood is doing the same.”

To suggest that there’s something inherently wrong about making films with a Chinese audience in mind would be ridiculous. It’s the push to make anything, and everything, with a Chinese audience in mind that worries people. Particularly Chinese people, I might add, considering that Chinese people are just people who want to be entertained, like every other person, and neither want every other country to conform to their government’s censorship standards or want their burgeoning film market to become Hollywood’s new lacklustre dumping ground. Potentially forcing smaller, homegrown, films out of cinemas prematurely, or altogether, as Hollywood does to the American market.

In some sense, Universal’s plan actually worked. Specifically in China, The Mummy garnered Tom Cruise’s largest opening ever. Beating some of the biggest Disney and comic book hits of that year and The Mummy’s own debut in North America, with the equivalent of $52 million. (Well over 60% of the film’s overall take from US domestic box office.)

A lot of this has been attributed to how much Chinese audiences like the idea of glamorous celebrity actors of Cruise’s calibre and the prospect of tomb raiding. The film also downplays a lot of its inherent qualities that might butt heads with censorship standards (the Chinese government’s censorship guidelines are infamous for their distinct dislike of the supernatural) while overplaying, and oversimplifying, elements which are popular in China but make North American audiences uncomfortable (like ISIS). Not that this meant that the film was actually that well received by Chinese audiences and, to come back to the situation which Garcia was describing, The Mummy was a noticeable, all round, turkey not just due to its brand recognition but also because of its price tag. The film was, if nothing else, as Garcia puts it “huge” and “costly”; seemingly for no reason other than to appear expensive.

Initial projections from the studio place the production costs somewhere around the $125 million mark but subsequent revelations made about the film’s production difficulties, spurring rumours that Tom Cruise took control of the project as an unofficial director (not an uncommon thing on Hollywood trainwrecks), have placed the cost range somewhere closer to $195 million.

$125 million is, already, an ungodly amount of money in relation to what audiences see on the screen. (You can chalk the extra $70 million up to sheer incompetence.) And you can’t help but feel that a talented director could have made that exact same film for half the money, if not less.

The idea that Cruise took control of principal photography, and maybe more, doesn’t make me like the film less. On the contrary, knowing that Cruise starred, did his own stunt work, directed and steered writing (even bringing in frequent collaborator Christopher McQuarrie to rework the screenplay) explains a lot of the film’s foibles. It was apparently Cruise who insisted that the plane crash sequence be filmed practically rather than digitally and, despite the film often coming off as a bit of a vanity project for an aging Cruise (there’s a point where Russell Crowe’s character describes Cruise’s as “a younger man” despite Cruise being two years older than Crowe), this shows how the film could’ve been substantially worse without Cruise’s input.

From a creative standpoint, the film’s most concerning quality is just how unoriginal it is. As it stands, film should already be a (no pun intended) universal language but the currency of Hollywood filmmaking today is intertextuality and brand recognition. When you take something with a culturally unique aesthetic and attempt to sell it to an audience that literally isn’t able to witness anything outside of a narrow window at the cinema (Hong Kong filmmaker Jevons Au described it as: “No ghosts. No gay love stories. No religion. No nudity. No politics”) then it not only encourages all of Hollywood’s worst habits it pushes forward to this state of a flavourless, meaningless, monoculture in studio film production. Case in point, the Uncharted connection.

Something else that a lot of people came to quickly realise about the film, before it was even released, was how much of a striking resemblance it bore to the video game series called Uncharted. Much like The Mummy, the games riffed off of the legacy and tone of the Indiana Jones films but the sheer number of identical design elements from the Uncharted games that feature in The Mummy, going right down to the film’s score, are remarkable. But the really stupid part is that the Uncharted games were also heavily influenced, on a fundamental design level, by the original Mummy films as well. The final stage of decades of creative inbreeding being an example of pure simulacrum: a copy of a copy of a copy which bears no relationship to reality and is therefore totally unaffecting to the audience.

Though Universal are quite renowned for snapping up rights to film adaptations of popular video games which they never actually get around to making, the Uncharted series is already owned by Sony. Who have a film studio which they’re finally trying to make something out of.

There’s no evidence that The Mummy ever did start out as some kind of a stab at getting the ball rolling on an Uncharted film, which was just repurposed, but this wouldn’t be the first time that both Universal and producer Chris Morgan have been suspected of this within the past several years; with Morgan’s screenplay for Universal’s integral franchise hit Fast Five being widely believed to have been repurposed from an aborted sequel to the star-studded 2003 remake of The Italian Job titled The Brazilian Job. Funnily enough, Morgan would team up with The Italian Job’s director and star for the eighth instalment of the Fast and Furious franchise in 2017.

Top: The Mummy (2017) Bottom: Uncharted: Drakes Fortune (2007)

Top: The Mummy (2017) Bottom: Uncharted: Drakes Fortune (2007)

Speaking of absurdly successful films that came out in 2017 starring Dwayne Johnson, Sony’s handling of their Jumanji sequel is perhaps the most demonstrative example of how easily The Mummy could have worked. Enough time has passed for 90s nostalgia to be big business (see Disney’s recent live-action remakes of their “renaissance” period) and if you get a talented director to take creative control, allow them to let their personal style shine through and to focus on building their characters, then audiences respond very well.

Sadly, The Mummy didn’t do any of this. It’s hard to tell if Kurtzman does have a directing style, it’s not apparent from The Mummy but that may be because he didn’t really direct it (and I, like most people, never saw his directorial debut People Like Us), while both Cruise and Cruise’s typical female on-screen sparring partner, Annabelle Wallis, seem to really struggle with understanding who or what their characters are. Wallis, particularly, is left to flail around awkwardly in her ad-libbed reactions to events in the scenes. Instead, it focuses on delivering moments that the film never earns and setting up sequels which will probably never be made.

None of these mistakes would be so bad if the public got the impression that they were mistakes that won’t be made again almost immediately. There’s a real cart-before-the-horse situation going on in Hollywood at the moment. It’s almost certainly related to the way in which Marvel Studios has fundamentally altered the makeup of cinema audiences today (the magic rock MacGuffin rears its head almost immediately in the film) and studios seem to be settling into the idea of going ahead with franchise plans no matter what, audience satisfaction be damned. The Mummy’s opening text quote, another trope of these new TV pilot films, reading: “Death is but a doorway to new life. We live today, we shall live again. In many forms shall we return.” Coming off as more of a threat to the audience than anything else. You can go ahead and not watch them, if you don’t want to, but they’re just going to keep making them anyway.

The Mummy is available now on DVD and Blu-ray.