From the undeservedly downtrodden to the greatest of trash. In no particular order, we count down the best horror films that may have flown under your radar.

Horror, the oldest and arguably most integral genre in cinematic history, has conquered the top of the box office charts and the lowest depths of the video store dungeons. Good horror is intoxicating and enveloping, it elicits completely illogical responses and can linger in our memories for a lifetime. It knows neither the boundaries of budget or constraints of common sense. This isn’t a competition to prove whose taste is more refined and whose eye more keen. Rather, these are films that I have come across that I found to be genuinely brilliant in their own ways and very rarely talked about so I hope to share them with people who love the genre as much as I do.

Uzumaki (2000)

Adapted from Junji Ito’s manga series of the same name, Uzumaki is a story about….spirals. Kinda. It’s a mystery that has little to no answers but a boatload of atmosphere and, most importantly, visual flare. You can see the fingerprints of the original manga all over this film from its use of framing and hyper-stylised characters to its remarkably off-colour humour. Not to mention the precise use of editing and performance that make it feel like a live-action anime. Imagine Eraserhead by way of Scott Pilgrim Vs The World. Uzumaki may not have the depth, or even sense, required to frighten you in the conventional fashion but it is expertly weird enough to crawl its way under your skin.

Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010)

This is a film for those who don’t mind style over substance or, more accurately, those who consider style to be substantive. Harking back, in both look and feel, to the new-age cultism and pseudo-scientific claptrap of the 1970s, this is a heady trip that is equal parts narrative film and MKUltra experiment. Beyond the Black Rainbow is an explosion of colour and weird, enthralling, subtext. Writer/director Panos Cosmatos, son of the infamous George P., said he wanted to recreate that childhood feeling of imagining what lay inside the horror movies at his local video store and, mostly, he succeeds. It’s a nightmarish response to mainstream Hollywood’s desire to dream of the past.

Your Vice Is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (1972)

Aside from the absolutely amazing title which (like most Giallo movies with such fantastically bizarre titles) has nothing to do with the plot, Your Vice is memorable for managing to reconfigure the sub-genre’s many tropes into something quite distinctive. The classics are all there: black gloves, black cat, killer POV, red herrings and that all important dream-like quality that so few have been able to capture. But on top of that its characters are so wretched, in nearly every sense of the word, that they add an air of authenticity to it. If you’ve blown through Argento’s good films and need something else to fill that Italian horror void then this has all the blood, sex and violence you could need.

Without Name (2016)

Lorcan Finnegan’s first feature-length film is a psychedelic slide into madness and, maybe, the best of modern day eco-horror that showcases nature’s dissatisfaction with humanity. No monsters, no gore and no jump-scares. The evil that lurks within the woods in Without Name communicates, pretty much entirely, through atmosphere as Alan McKenna’s land surveyor (an, already, unusual thing to see in a film) begins to crack under the weight of his own guilt regarding his family, his job and his affairs. As he digs deeper into the cursed forest that he’s surveying for dubious reasons, and deeper into his beleaguered conscience, the more he understands the terrible price he has to pay.

Targets (1968)

Perhaps not horror as you would classically think of it, Peter Bogdanovich’s little-remembered film asks some much broader questions in that unmistakable Movie Brat style. Boris Karloff, in full on thespian mode, plays a fictional version of himself, that has grown weary of the Hollywood horror machine, while a baby-faced young man from suburban LA smiles and eats his veggies while silently plotting a murder spree. Karloff’s drama of artistic integrity may not thrill you but Tim O’Kelly’s unforgettable performance as a Great White All-American Psycho is as entrancing as it is chilling and the inevitable crossing of their paths produces a thought-provoking moment of understanding.

The Man Who Laughs (1928)

Part romantic drama, part epic historical fantasy, Paul Leni’s adaptation of Victor Hugo’s novel defies precise classification but Roger Ebert may have put it best when he wrote: “The Man Who Laughs is a melodrama, at times even a swashbuckler, but so steeped in Expressionist gloom that it plays like a horror film.” It’s easy to see how the brilliance of it passed so many by for so many decades before its contemporary reappraisal as one of the most significant horror films ever made.

The Man Who Laughs arrived at an odd, and very important, nexus point in the development of both cinema, and pop culture, as we know them today. The protagonist’s design, brought to life by Jack Pierce (who would go on to design the definitive representation of Frankenstein’s monster in Universal’s 1931 film with Boris Karloff), is cited as the inspiration for the classic comic book character The Joker and the Gothic sets were the framework for art director Charles D. Hall’s work on Universal’s defining monster movies in the 1930s; from Dracula to Bride of Frankenstein.

The Legend of Hell House (1973)

This film is essentially what you’d call a rip-off, but what a rip-off. Tonally and thematically it’s a near carbon copy of Robert Wise’s The Haunting. Now, if you haven’t seen the original Haunting I implore you - seek that out first. It is, in all respects, a masterpiece and an integral part of cinematic horror history. But if you have seen it and enjoy its slow burn of psycho-sexual horror then you will find a lot of the same things to enjoy here, albeit in a slightly schlockier way but that’s all part of the fun. It’s adapted by Richard Matheson from his original novel, so while the visuals may be giving you the entertainment of a theme park haunted house the script never descends into absolute hysteria.

Alice, Sweet Alice (1976)

When an adorable, ten-year-old, Brooke Shields is the first victim in your slasher movie then you know you’re in for quite the disturbing ride. Playing out a little like Don’t Look Now, but without the taste, Alfred Sole’s grimy B movie would come off as derivative if it wasn’t so strikingly unconventional. It’s a whodunnit that fully reveals its killer at a wholly odd point in its story and a gory denunciation of Catholicism that, for the most part, comes off as quite melancholy. (Sole had been formally excommunicated from the church a few years prior to making Alice, Sweet Alice and the film’s original title, one of several from various re-releases, was Communion.)

Dead End (2003)

The key word with Dead End is simplicity. It’s a simple story, in a simple location, with some pretty simple characters but it has an odd staying power. It’s a camp-fire tale, a Lady in White story to be exact, something teenagers would tell each other with a flashlight pointed underneath their chin. It’s very reminiscent of the old Goosebumps TV show (or Are You Afraid Of The Dark, if you can remember that). It has a “if it ain’t broke” attitude to ghost stories and you can kind of see its point. Less equals more in this kind of storytelling and its limitations often end up working to its benefit.

Onibaba (1964)

Kaneto Shindo’s film of women trying to survive in the war ravaged landscape of 14th century Japan is a sweaty heaving mass of masterpiece. Shot beautifully and performed flawlessly, it’s a terrifying parable of greed, lust, desperation, betrayal, death and, above all else, fear. Shindo’s masterful weaving of Japanese cultural heritage and psychoanalytical subtext make for a complex experience that you can feel your way through with no expert knowledge. A deliberate style perfectly reflected in the brilliant score, part traditional Japanese drums and part 60s jazz.

Lovely Molly (2011)

Eduardo Sanchez goes back to the horror basics that made his first film, The Blair Witch Project, so successful. With no jump scares, and virtually no shocks at all, Lovely Molly relies pretty much solely on atmosphere and the power of sound editing to frighten you. Horror stories that manipulate expectations to focus on the psychological deterioration of their protagonists became all the rage in the wake of Lovely Molly, but it rarely gets credit for being ahead of the curve. Minimal on both locations and cast members, it has a genuine sense of unease to it. The jewel in its crown being a stunning lead turn from unknown actor Gretchen Lodge in a remarkably demanding role.

Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971)

The rule of thumb with Dario Argento is: if it came out in the 70s then it’s probably a masterpiece, if it came out in the 80s then it’s probably very good and if it came out after 1990 then it’s probably absolute garbage. Four Flies on Grey Velvet came out in 1971, so, while Argento may not not have been quite at the height of his abilities, he was at the pinnacle of his youthful creativity. The fantastic soundtrack, from Ennio Morricone, underpins the joie de vivre that Argento applied to the film. This is not the work of a full-fledged master but, rather, the work of a budding one. Bursting with ideas, and with everything to prove, this is sometimes called Argento’s lost masterpiece. That part is debatable but it is clearly one of his most energetic, and innovative, films.

Isolation (2005)

Killer cows? Not quite, but close. Billy O’Brien’s creature feature sees a failing farmer make a deal with the mad science devil to gestate unholy abominations inside his cows and the results are actually pretty darn scary. Sporting a killer cast, some great practical effects work and a noticeably brilliant score, Isolation is an often overlooked British gem. It’s midnight monster survival madness but the people making it took it seriously enough for it to pay off. O’Brien’s new horror film, I Am Not a Serial Killer, is also reviewed in this issue.

Sisters (1973)

Brian De Palma’s first foray into the world of thrillers was violent, bloody, shocking, stylish and he never looked back. His emerging flair for the spectacularly macabre in Sisters is very comparable to the similar emulation for Hitchcock’s darker side happening in Europe at the same time, with the emergence of Dario Argento. You could, in fact, very comfortably call this American Giallo. The flamboyance, the structure and the sense of humour are all there. It’s a must for fans of De Palma and, especially, his early horror films like the cult classic Phantom of the Paradise (De Palma’s following film). A prime example of a distinctive director discovering their own style.

Amer (2009)

This is for people who think they’ve seen all that Giallo has to offer them. Amer is a horrific story of sexual discovery told in three parts; from youth to adolescence to adulthood. Visually striking and scored magnificently in the funky, playful, spirit of Giallo classics, it finds ways to be avant-garde in a genre made stale by rigid set-ups and payoffs. This is not for people who need every film to have a plot, in fact it’s mostly devoid of dialogue and told primarily in extreme close-ups. Amer is an experience that assaults your senses as much as it indulges them.

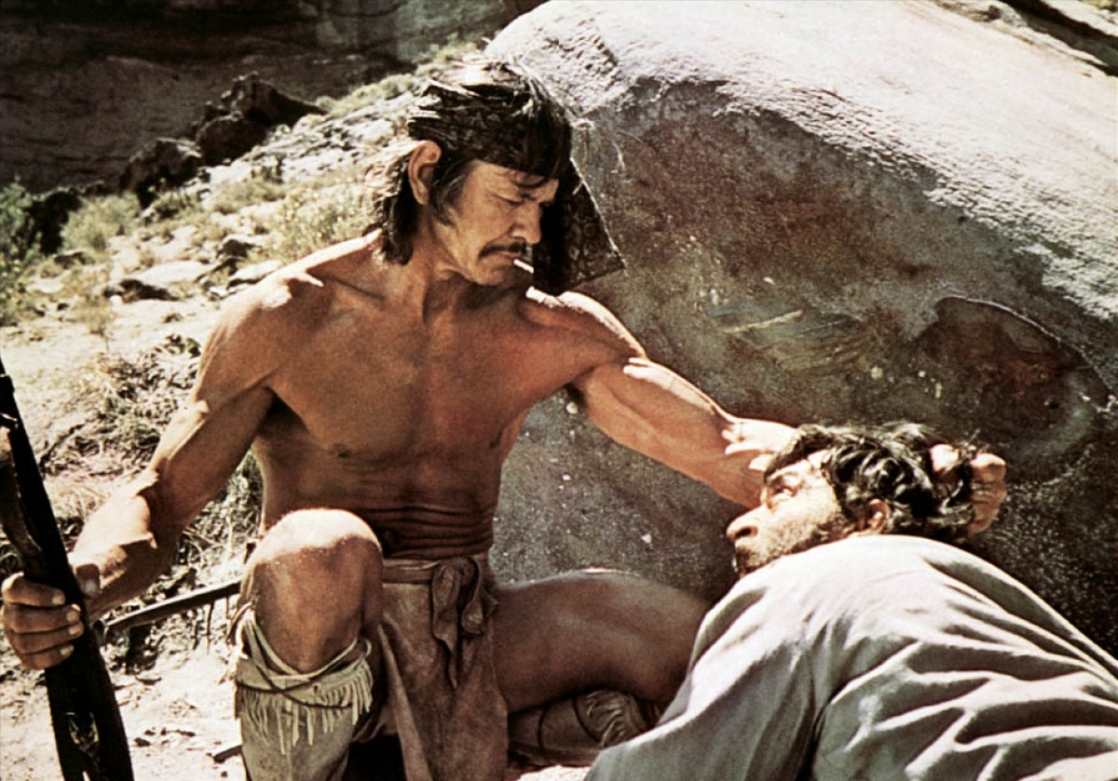

Chato’s Land (1972)

Charles Bronson and Michael Winner enjoyed a string of successes together. Their debut (the first of three films that the duo would release in the space of eighteen months) was a Western called Chato’s Land about the eponymous Chato, a Native American hassled to the point where he commits murder and flees into the desert. Chato is pursued by a posse lead by a former Confederate officer and this is where it ceases to be a Western and becomes a horror film.

Chato’s Land goes beyond simple exploitation and examines the dynamic of a mob who end up committing atrocities. From those who think they’re doing it for justice, those who think it’s their duty, those who just want to kill and to those who are too afraid to resist the group. Some have drawn parallels between the film and the United States’ then-current experiences in Vietnam. This is debatable but it’s undeniably a disquieting tale of men who go searching for death - and find it.

The Collector (2009)

You’d be forgiven for seeing this on the shelf and dismissing it as a cash-in on the creative killer/torture porn fad of its day, which it is - but with a little twist. The Collector is a film about a cat-burglar who decides to rob a house on the same night as a Jigsaw-esque killer invades it to torture the occupants and set devilish traps. What ensues is a cat and mouse game played out in a slasher setting and, for anyone who’s grown weary of mainstream horror’s passive protagonists, this is a thorough hoot; not to mention a precursor to films like You’re Next. The sequel never lives up the standard set by the first but it does keep the spirit of B movie fun alive. If you do end up watching both, make sure to stick around for the connected pair of post-credits stingers.

Escape from Tomorrow (2013)

It’s far from perfect but there quite simply isn’t another film out there like Escape From Tomorrow. Writer/director Randy Moore felt a special connection to a location, in which he wanted to shoot his horror film. The problem was that this location is possibly the most copyrighted, image-controlled, place on earth: Disneyland. In what was dubbed an unparalleled act of guerilla filmmaking, Moore and his team secretly filmed a horror film in both Disneyland and Disney World without the knowledge of anyone working at the Disney corporation, let alone the theme parks themselves. Moore’s film possesses a feverish, dreamlike, quality, not dissimilar to the early films of David Lynch, that’s compounded by the uniqueness of its location. Escape not only captures a fleeting, nigh-on impossible to recreate, experience but it also flips it completely on its head.

Hierro (2009)

From rising Spanish star Gabe Ibáñez comes this haunting little film about a missing child and a mother’s need to find him. By restricting the film to a remote Spanish island, Ibáñez manages to recreate the slow-burning dread that his contemporaries have achieved in the distinctive style of modern Spanish horror while, at the same time, evoking the harsh landscapes that have served European masters so well. Gorgeously shot and with a brilliant lead performance from Elena Anaya, Hierro recalls De Palma, Roeg and maybe even a little Antonioni. It’s a lot harsher than most of the recent Spanish successes and it stands apart because of it.

Saturn 3 (1980)

A stellar cast, a high-concept sci-fi horror script from Martin Amis and the producing talents of some of the key figures behind some of the biggest films ever made. What could go wrong? Everything. Everything went wrong. Saturn 3 may be a failure but, god damn it, it’s a magnificent failure. The production was littered with troubles which resulted in some truly bizarre creative choices being made. Amis’ 1984 novel “Money” is supposedly a fictional retelling of the ordeal.

A good example would be when original director John Barry (of Star Wars) was replaced by Stanley Donen (of Singin’ in the Rain) only to have him disapprove of antagonist Harvey Keitel’s thick Brooklyn accent so much that he re-dubbed his entire performance with another actor. The result only adds to the film’s eerily nightmarish quality. It’s a satisfyingly weird trip of psycho-sexual obsessions and grotesque body horror, containing one of cinema’s most memorable killer robots. Think “the Pixar lamp’s demonic cousin” and you’re on the right track.