A brief history of an unconventional filmmaker and his unsung influence on Italian Cinema.

When contemplating the everlasting beauty of Italian Cinema, one stereotypically envisions the films of Frederico Fellini or Roberto Rossellini, the grandfathers of neorealism, who brought us images of grandiose and suave men pursuing elegant and refined women down cobbled streets of effortlessly picturesque Italian cities; lives of enjoyment in excess and the pursuit of splendour above all else. This representation of 1950s/60s Italy has remained the dominant iconography for the saga and pervasive influence of Italian filmmaking, justly categorising the country as the motherland for some of the most influential directors in film history. However, missing from this reflection are the other discounted facets of the country’s long-held love affair with film, the many genres tackled by Italian filmmakers that are continually disregarded; the ubiquitous evolution of the Italian Comedy or reimaginings of Hollywood’s chiaroscuro Noir, for example, all with the habitual undercurrent of societal observation that is so prevalent within this nation’s culture.

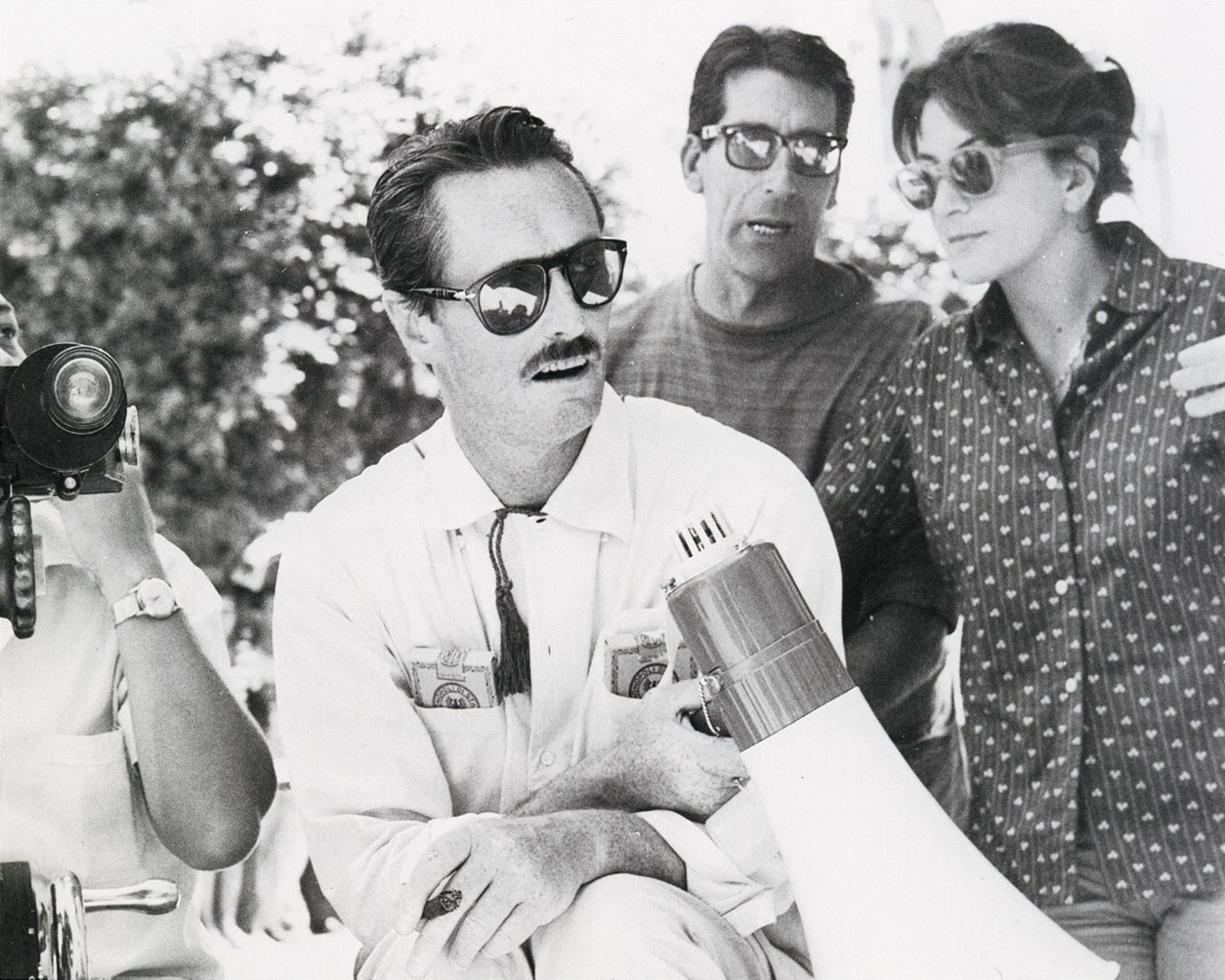

Italian auteurs have historically exploited the visual medium for the benefit of self-reflexive commentary and promotion of self-awareness in their own people, necessitated by the tumultuous history of the country and the subsequent transitional social structures that affected and altered its populace. One director ferociously pursued this objective with unyielding cavalier observation and wry intelligence, faced widespread social critique with noteworthy defiance and yet is still, unfortunately, under-appreciated outside the land of archetypal lovers; the Genoa-born actor/screenwriter/director, innately versatile and sorely missed creative, Pietro Germi.

Beginning his career as an actor, Germi entered the world of decadent filmmaking at the infamous Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia School in Rome under the tutelage of renowned neorealist director, Alessandro Blasetti. After a few successful attempts at working in front of the camera, he eventually decided to remain primarily behind it, and his directorial debut was in 1945 with crime narrative, Il testimone (The Testimony).

Beginning his career as an actor, Germi entered the world of decadent filmmaking at the infamous Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia School in Rome under the tutelage of renowned neorealist director, Alessandro Blasetti. After a few successful attempts at working in front of the camera, he eventually decided to remain primarily behind it, and his directorial debut was in 1945 with crime narrative, Il testimone (The Testimony).

From here Germi worked extensively within a neorealist, Noir framework, and four years later received critical recognition across Italy with In nomme della legge (In the Name of the Law, 1949), earning three Nastro d’Agento Awards at the Venice Film Festival. One of the first Italian films to discuss the Sicilian Mafia and co-written by Fellini, it depicts the trials of a young magistrate from Palermo who is sent to serve a small Sicilian village and forced to fight the various social injustices that repress its citizens. Germi proved his directorial prowess with this film, evident in the stunning photography captured, equally comparable to the expansive, spectacular cinematography of John Ford’s Old West.

His many successes within the neorealist genre eventually gave way to an alternative creative emphasis, where his ingenuity and ability to create films brimming with social commentary would flourish immensely. During his final expedition into film noir, Un maldetto imbroglio (The Facts of Murder, 1959), Germi both directed and occupied the role of the film’s protagonist; the brilliantly debonair Inspector Ciccio Ingravallo. Adapted from the novel by Carlo Emilio Gadda, entitled Quer pasticciaccio brutto de via Merulana (That Awful Mess on Via Merulana), his portrayal of the lead, instilled with an alluring sense of stoic masculinity, rivals any stereotyped Hollywood depictions of isolated, surly and misunderstood detectives. His next ambition would be to tackle social satire through the use of comedy, abandoning unnerving realism for a more light-hearted approach, however one that would still entice the same cogent impression on its audience. This began with Divorzio all’italiana (Divorce, Italian Style, 1961), which severely examined the restrictive lack of a divorce law in Italy. We witness the ludicrously apathetic hero (or perhaps antihero), portrayed by the charismatic Marcello Mastroianni, go to extensive lengths to rid himself of his unhappy marriage. He attempts to orchestrate an affair between his wife and her ex-lover, to catch them in the act and take advantage of the Sicilian honour code, wherein a man could have received a reduced sentence if committing murder as retribution for his ‘offended honour.’

The film was an international sensation and received a deserved Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, nominations for Best Actor (Marcello Mastroianni) and Best Director and was entered into the 1962 Cannes Film Festival. His most avid contemporary fan is Martin Scorcese, who wrote an essay for the Citerion Collection DVD release of the film and which is, sadly, still only available in North America. Scorcese, in fact, heralded Divorzio all’italiana as one of the main inspirations for his work, and particularly for his Mafia classic, Goodfellas.

Germi’s unforgiving portrayals of hypocritical morality within the supposed modernised Italy of the 1960s were a far cry from the other internationally popularised Italian films from the era. Germi continued in this merciless vein with two more features, Sedotta e abbandonata (Seduced and Abandoned, 1964) and Signori e signore (The Birds, the Bees and the Italians, 1966).

In the first two, Germi showcased the out dated customs and fashions of the Southern regions, the stark disparity between the North and South and the actuality of disproportionate prosperity during the 1960s. For this he received an immense backlash from those who accused him of discriminating against Sicilian values and history, leaving the North free from any denunciations of sanctimony. To this he responded with the third narrative, which focused on the atrocities committed by the bourgeoisie of the Northern city of Treviso in order to underline the issues in Italian society nationwide.

The unofficial ‘trilogy’ depicts a country that struggled to consolidate its rural, primitive past with the more developed and industrialised way of life fomented by the ‘economic miracle’ of 1950 – 1970. This tumultuous era of change saw the trade of manufactured goods increase sixfold and consequenced a newfound consumer culture that emphasised the already existing incongruence between the agricultural workers of the South with the middle classes of the North. The films were imperative, allegorical studies of the delusional and turbulent battle between the deep-rooted, archaism of Italian culture and the modern liberalisms of the 1960s.

The three films distinguished Germi’s signature grotesque comedy style and an entire film genre, commedia all’italiana (comedy Italian style), owes its name to his significant and unabashed satire. It would become the novel popular genre for years to follow and instigated a movement away from neo-realism. Italy was ready to laugh again and during the commedia all’italiana era, proudly subjected its worst features and flaws to an emphatically amused audience.

After these, arguably his most important collection of films, Germi directed four more features before his untimely death in 1974 from hepatitis. His final work was entitled Amici miei (My Friends) and surrounded four middle-aged friends struggling to accept their adulthood within the ornate city of Florence. He was regrettably unable to complete the project and his close friend and colleague, Mario Monicelli, finished the film after Germi passed on; it was released a year later and dedicated to Germi in his honour.

Germi’s unique motivations allowed for the serious and destructive issues his films examined and exaggerated to be jubilantly ridiculed to the point of utter irreverence. His playful use of rhythm and comedic timing culminated to create an energetic yet crude depiction of the imperfections within 1960s Italy. Germi was a brave director, fiercely anti-Communist unlike his luminaries who were largely Marxist or left-wingers, and unafraid to question contemporary Italian society.

A true black comic and eccentric outsider, his films were not made for international distribution or appreciation; they are for Italy and its citizens, a record of their history, and yet, are nonetheless representative of the unparalleled distinctive talent of Germi. They remain eternally entertaining and deserve, unequivocally, to stand amongst the universally proclaimed ‘greats’ of other Italian filmmakers, and besides, who needs realism when you can laugh instead?

For more info about Pietro Germi’s work please refer to: https://mubi.com/cast/pietro-germi or http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0314584/