We break down and explain the religious and cultural themes that make up the philosophy of Tron, from Steve Jobs to ancient Chinese texts.

In a time where it may be nigh on impossible to avoid the overt commercialism of Disney-owned franchises, which are already pretty commercialistic as it is, it can do you the world of good to remind yourself of the virtues of one of the weirdest and most awkward of all the intellectual properties to come out of Disney’s, unofficial, weird and awkward sci-fi department - the Tron series.

While plans for a third film were scrapped in the wake of one of this department’s frequent financial failures (Brad Bird’s Tomorrowland) it did expand to TV but we’ll just be talking about Steven Lisberger’s 1982 original film and Joseph Kosinski’s 2010 sequel. Which is good because they’re packed with far more subtext than one would expect from something with such a silly reputation. So, without much further adieu, let the games begin…

Buddhism

Like many, perhaps even most, Hollywood spectacle epics, religion is a principal theme of the Tron films but what makes them so interesting to rediscover is how they eschew the standard biblical narratives for heavy buddhist themes. Tron Legacy adds much more overt references to buddhism in the film’s dialogue, referencing famed Tibetan spiritual teacher Chögyam Trungpa by paraphrasing one of his most famous quotes, “Chaos. Good news.”, and even name dropping his most famous work, Journey Without Goal.

Lisberger’s original, however, contains more subtle visual references. Some have compared the bright visual patterns which appear during Flynn’s entry and exit from the computer world to the mandala, an intricately designed spiritual symbol which is prevalent in both buddhism and hinduism, symbolising metaphysical realms; particularly microcosms.

The computer realm, or Grid, of Tron’s universe of course being, like all fantasy realms really, a symbolic representation of our outside world seen when in some kind of dream, or trance-like, state which the mandala is used as a gateway to; demonstrating both society’s structure and order through metaphorical designs. One of the key structures which the Tron films represent being our next talking point….

Anti-Capitalism

Financial squabbles are the initiating conflicts behind the stories of both Tron films, specifically the theft of intellectual property by a large corporation, and they emphasise the purpose of technology in society beyond profit and control.

In Tron Legacy, the initial dispute revolves around the intellectual property and vision of Kevin Flynn which has been repackaged and corporatized in his absence, charging the consumer for no reason and operating entirely for profit. His son, Sam, breaks into the main building of his father’s company and steals their newest operating system (described by their CEO as different from the previous iteration because this year they “put a twelve on the box”, as a dismissive retort to being questioned over improvements in the product in relation to the rising fees charged to students) and shares it for free on the internet.

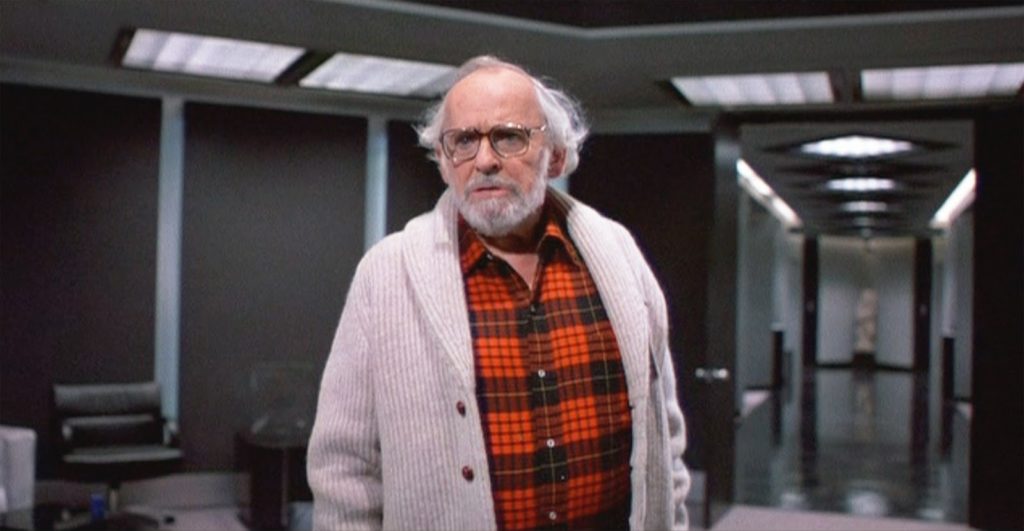

To be clear, neither film really endorses a political or social ideology beyond capitalism (these are Hollywood films, after all) and the side of the line that they fall on is more Free Market economics. Most of this subtext stems from Lisberger and the time in which Tron was originally made; commenting on the “Woodstock” vibe, as he puts it, within the American tech industry at that time. It’s certainly something which has permeated into our overall, modern day, view of the mythology surrounding the American tech industry. Encom’s co-founder, the typical caricature of the flannel shirt wearing California hippie, Walter Gibbs being a strong visual representation of this.

He argues with Encom’s slippery senior executive, Ed Dillinger, that “user requests are what computer’s are for”, to which Dillinger snaps back with “doing our business is what computers are for”. Dillinger going on to tell him Encom isn’t the company he founded in his garage anymore, a part of the California tech legend that extends all the way to Steve Jobs.

Jobs’ legacy being, no pun intended, a huge part of Tron: Legacy’s genetic makeup. Kevin Flynn, now steering Encom after the events of Tron, becomes an iconic public figure who holds enormous press rallies with mission statements and visions of the future only to have that part of him, literally, break free and become his undoing in the form of the film’s villain, Clu. The relationship between these two characters exemplifying perhaps the films’ biggest theme.

Taoism

In Lisberger’s original Tron, Walter Gibbs’ computer world doppleganger, Dumont, offers a line of cryptic wisdom lifted straight from the I Ching, which sits next to Journey Without Goal on Kevin Flynn’s bookshelf in Tron: Legacy: “All that is visible must grow beyond itself and extend into the realm of the invisible”. It serves as a reminder of how eastern philosophy runs through Lisberger’s original vision of Tron and runs into the sequel; from Kevin Flynn’s “zen thing, man” to the common yin yang relationship which he has with his alter-ego and nemesis, Clu.

One of the most prevalent aspects of this, however, coming not out of conflict but precisely the opposite. In his old age, Flynn comes to be a proponent of perhaps the most defining philosophy of Taoism: wu-wei, commonly translated as “action without action”. Flynn’s attempt to forcefully “reshape the human condition”, as he puts it, creates Clu and the failure and imbalance at the heart of the film’s conflict whereas his success in this area, Quorra and the divine Isos, appears naturally within the Grid; as almost by the will of the universe.

As well as actively engaging in meditation, Flynn also encourages non-action; telling Sam “it’s amazing how productive doing nothing can be”. Then, at the film’s turning point at the beginning of the third act, he encourages Sam to be still and wait again which results in the illumination and discovery of the solar sailer, which transports them to the final destination of the journey and the resolution of the conflict. Here, Flynn finally reintegrates Clu into himself; achieving a state of Oneness denoted by the yin yang symbolism and the Tao. A spiritual, and narrative, resolution that can be found in numerous popular works of modern American film which draw heavily from Eastern philosophy and tradition; such as the journeys of Neo, to become the literal “one” in The Matrix, and Luke Skywalker in The Last Jedi.