We stack Pacific Rim Uprising up against its progenitor, comparing it in all fields, and the results don’t quite sync up.

I wasn’t a particularly big fan of Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim when it first came out but, over the years and like with most of del Toro’s films, I’ve come to appreciate it for what it is - an incredibly detailed, and lovingly crafted, film.

At first, I didn’t really understand what Pacific Rim was. I was expecting del Toro to fuse the elements of Eastern and Western storytelling together into something original. (This was back before I understood that del Toro doesn’t really do original.)

What he did wasn’t to fuse Japanese animation into Hollywood filmmaking. Instead, he took all the tools that Hollywood could give him and used them to perfectly recreate Japanese animation. Every single decision that del Toro makes as a filmmaker (the characters, their names, their mannerisms, the lighting, the framing, the designs, the music, all of it) would be the same one made by someone making a Japanese anime.

You can argue over how important it is but del Toro is, undeniably, a master of worshipping at the feet of genre. Pacific Rim was made in service to the genre, to celebrate something larger than itself. And that makes its 2018 sequel, Pacific Rim Uprising, all the more depressing of an experience as that film primarily serves itself.

When the score is tallied, Pacific Rim Uprising probably won’t be among the worst films released in 2018. It probably won’t even be among the worst films in 2018 that are sequels. But, when you’re judging a sequel, you have to weigh it against its predecessor to create some kind of a relative scale. (A bad film can still receive merit for simply being better than its predecessor.) As a film, Pacific Rim Uprising is workaday Hollywood fluff. As a sequel though, it’s abominable.

Pacific Rim Uprising isn’t one of those sequels that just fails to live up to the standard of the original. In its laziness and bumbling, it actually goes so far as to make the original worse too.

Its leading man

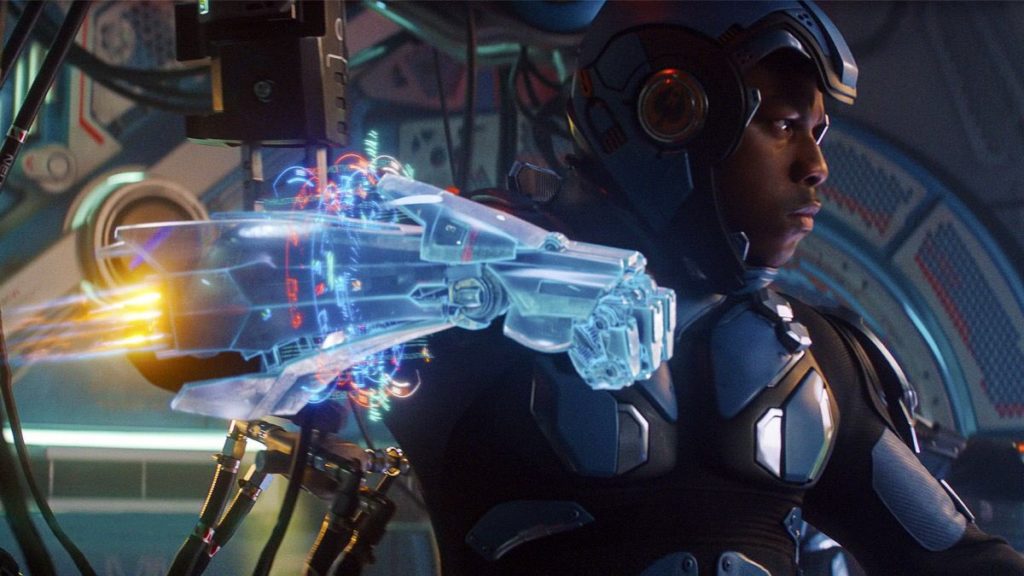

As complete as del Toro’s film was, overall, there was arguably a lot of room for expansion. One of the things that becomes abundantly clear within the first few minutes of Pacific Rim is how ripe the world that del Toro creates is for a prequel. As the sequel project began to take shape, adding John Boyega as a leading man who sports the same moustache as Idris Elba’s character from the first film (one of the original pilots of the film’s storyline), that seemed to be the way things would go. Instead of playing young Stacker Pentecost in a prequel though, Boyega instead plays the son of Elba’s character - Jake Pentecost.

It’s the first piece of new information that we get about the new story after the opening minute of the film (which is just footage from the first film) and it’s an ominously bad sign right off the bat.

Again, one of the best things about Pacific Rim was how unflinchingly it stuck to the anime approach to characterisation. Stacker Pentecost, Raleigh Becket, Hercules Hansen. These aren’t real people, they’re an anime’s idea of real people. They’re completely removed from the way in which Westerners would usually choose to depict themselves in media. Jake is not.

Boyega is a budding mega-star. With his feet firmly in the new Star Wars films, he’s quickly becoming a household name and he’s hunting for the leading man roles that make ordinary actors into action heroes. With a producing credit on the film, it seems like he was pretty invested in the project and the performance which makes you feel like it was all his decision when he uses the opportunity to pretend to be a Hollywood action star rather than being his own.

One thing which began to become noticeable about Boyega a few months prior, in Star Wars: The Last Jedi, is how much he’s trying to define his screen persona as someone who ad libs a lot. It’s one of the chief characteristics of Hollywood superstars who essentially go on to play themselves in every film. It’s commanding, scene stealing, confident and a clear sign of talent.

In order to flesh out this point, now would be a good time to bring up the major Hollywood connection that Pacific Rim does have, aesthetically speaking.

It’s basically a remake of Independence Day 2

One of the unfortunate side effects of del Toro’s dedication to genre is that it makes his films incredibly predictable. Anyone familiar with the genre that del Toro’s emulating can, and very probably did, easily guess the ending of del Toro’s last three films.

When you settle into Pacific Rim, it becomes clear what Western framework del Toro had decided to hang his film on. You sit back and think: “Oh, I know this. It’s Independence Day. I remember Independence Day, yeah. So this will end with an alien with a big, flat, head looking at something nuclear counting down before it explodes and saves the entire world.” (Which it does.)

Bearing this in mind, the similarities between Pacific Rim Uprising and the belated 2016 sequel Independence Day: Resurgence become increasingly apparent. Right down to the final scene, in which the good guys promise a turning of the tables, where the humans travel to destroy the aliens, in a sequel which will almost certainly never be made because this film puts everything in its cart before its horse.

In Independence Day: Resurgence, Jessie T. Usher plays the son of Will Smith’s character who, like Elba’s character in Pacific Rim, was a military hero and leader from the previous film’s conflict. (The role which defined Smith as a Hollywood star - ad-libber, comedic, compelling, relatable, rough n’ tumble, easy to work with.)

Leaving out how incredibly low a bar Independence Day: Resurgence is to set yourself, creatively speaking, and bearing in mind that I can honestly say that I personally enjoyed Independence Day: Resurgence for being an actual resurgence of Roland Emmerich’s famous 90s style - the comparison really serves to highlight how stagnantly formulaic Pacific Rim Uprising is.

Much in the same way that Usher never fills the shoes of his character’s father, despite that precise thing being his character’s intended arc, Boyega also fails to do so. And not just because of miscasting. In a very similar cart-before-horse situation, Independence Day: Resurgence also suffered from one of Pacific Rim Uprising’s most fatal flaws - overcrowding.

As Usher was, Boyega is partnered up with a shifting array of loosely connected side characters including (but not limited to): a handsomely square-jawed blonde male co-pilot with whom he has a rocky personal history and must reluctantly work with again, a male scientist from the first film who is motivated by their residual psychic connection with the alien species antagonists of the first film, a male Chinese commander who is blown up in his command centre by the alien antagonists and a plethora of underwritten youngsters who are incidentally all top gun pilots.

Boyega never gets to fully establish an affecting relationship with any of these characters because there simply isn’t time to. Every time a new plot thread starts, the story shifts gears to another conflict within the film and they’re mostly comprised of just really annoying bickering between two characters that you don’t really know.

It might be Pacific Rim Uprising’s most insurmountable fault, which is that it’s a hundred minute film that feels like an eternity. To call them pacing issues would feel like an understatement. One of the film’s most undeniable successes is its animation for the fight scenes (the real unique selling point of the film, no matter how you look at it) but, when viewed as a whole, they feel largely infrequent. Most of the film is expositional dialogue.

Too much junk

One of the precise elements that del Toro captured from Independence Day, that made Pacific Rim work so well, was the satisfying sensation of simple story structure. Completed arcs. Payoff. Pacific Rim Uprising’s insistence on cart-before-horse doesn’t just screw up the characters, it screws up the basic act of storytelling.

Around half way through the film, it’s revealed to the audience that Charlie Day’s character has secretly been brainwashed into becoming the main antagonist of the film but the film continues to play out as if the original red herring scenario that it develops in the first hour of the film (including the time after it’s unmasked) is still going, making the exact same reveal almost twenty minutes later. It’s jumbled and meandering. There’s too much meaningless sizzle compared to meaningful plot.

To come back to the very beginning of the film, where it gets off on the worst start imaginable, the actual film opens, after the initial minute of old footage, with some B-roll of Boyega raging at a wild pool party before cutting to him asleep on the back of a Jet Ski in the pool the next morning. The footage lasts for thirty seconds before a change in music and tone.

There’s nothing that the footage says that isn’t made clearer, and more concisely, by that cut to Boyega asleep on the Jet Ski. It’s a more thought-out pull back shot, to reveal the information that he’s narrating, which is sped up and cut to ribbons; like the rest of the film. (There’s an incredibly painful crash-zoom montage later on that epitomises the film’s inability to smoothly relay information to the audience.)

This shot is then immediately followed by three front-and-center, back-to-back, product placements. (Boyega goes so far as to lovingly kiss one of them.) It happens a lot, this sensation of B-roll and outtakes making it into the final cut despite them being of no value. This is apparent none more so than when Boyega ad libs. Most of it is just awkward but there’s a particular scene, where Boyega tries to do an impression of Scott Eastwood’s character (which should have been moderately easy considering that Eastwood is essentially doing an impression of his own father in this film) to Rinko Kikuchi’s character and her pitying, forced, laughter in the dead silence of the scene seals it as one of the most painful moments in any recent blockbuster.

But it’s their characters’ relationship that makes Pacific Rim Uprising a film that miraculously reaches its hand back in time to make the original Pacific Rim a worse film.

What they did to Mako Mori

Kikuchi’s is the only main character from Pacific Rim to return for this film (Charlie Day and Burn Gorman’s scientists being side characters at best) and, of all of the main cast, she might be the worst one to bring back and definitely in the way that they did.

Kikuchi’s Mako Mori was Pacific Rim’s only lead female character but she was also its most interesting. Her arc, and growth, augments not just the characters around her but the film itself. Her relationship with her adoptive father, Stacker Pentecost, enriched both of their characters to their fullest extents. To discover that Pentecost not only had a younger, biological, son, who is never mentioned or referenced one single time in the course of the original film, completely ruins the defining relationship of that film. Jake Pentecost, simply by virtue of existing, not only doesn’t add anything to the overall story - he actually subtracts from it.

This isn’t the only instance of this either. After decimating your understanding of the characters and their relationships from the first film, Pacific Rim Uprising goes on to retroactively alter the central plot of Pacific Rim to the point where it no longer makes sense.

The whole third act is gibberish

One of the original film’s plot points that Pacific Rim Uprising does, doggedly, stick to is the moment when doctors Gottlieb and Geiszler “drift” with a Kaiju brain, learning their overall objective in the process (exactly like it happened it in Independence Day, yes, tentacles and everything). They learn that the monsters have masters who are essentially using the Kaiju to clear out populated areas.

But suddenly, in Pacific Rim Uprising, Boyega’s character susses out something, seemingly from a wild hunch based on absolutely nothing other than the third act needing to ramp up to the finale, that nobody in the first film, or the intervening decade, ever figured out from rudimentary observational data. Which is that the monsters were all, actually, just trying to make it to Mount Fuji so that they could jump into the volcano and blow it up with their highly explosive monster blood.

Setting aside just how convolutedly stupid that is even for a film about giant robots punching one another, it just makes no sense based on anything that you saw, or heard, in the first film. You don’t know exactly where the so-called interdimensional “breach” lies in the Pacific ocean but you assume it’s somewhere in the middle; which is how the Kaiju attack cities in America, then the Philippines, then Mexico, Australia, China.

If you’re in the Pacific ocean and have a direct mission to go straight to Mount Fuji then how in the name of Charlie Hunnam is going via San Francisco the best route to doing that? Why would you stop off in Manila when you’ve already swum the vast majority of the way to Japan? It makes absolutely no sense and the film just drops it on you to manufacture a new ticking clock for the film’s final battle.

I’ve singled out the characters already but really nothing about this film is adequately built up to or delivered. It’s possible that this is mostly because of the experience of the director involved.

The captain of the ship

Guillermo del Toro was replaced as director, and co-screenwriter, by Steven S. DeKnight [pictured above]. While del Toro had seven feature films under his belt as a director before he came to Pacific Rim (all of them, arguably, modern classics and one or two undeniably so), DeKnight had none.

DeKnight is probably best known for being producer and showrunner on Netflix’s highly successful comic book TV show Daredevil. Compared to del Toro as a director, he had, to del Toro’s seven feature films, seven episodes of various TV shows spread out over the preceding fifteen years.

This isn’t to say that the work that DeKnight was doing up until becoming a feature film director was immaterial, or that he won’t go on to direct a good feature film later in his career, but it certainly explains a lot of the film’s fundamental problems.

Guillermo del Toro, for better or worse, is always a film director. He works in TV all the time as well, but when he makes a film - it’s a film. Something worthy of the cinema. They have a size, and a scale, and a level of quality of their own. But the game in Hollywood right now is to spin franchisable films off in as many directions as humanly possible. As DeKnight put it himself:

“The plan was always to use this movie as a launching pad. If enough people show up to this, we’ve already talked about the plot of the third movie, and how the end of the third movie would expand the universe to a Star Wars/Star Trek-style [franchise] where you can go in many, many different directions. You can go main canon, you can go spin-offs, you can go one-offs.”

There’s nothing wrong with “TV quality”, in and of itself, but it’s not what people usually pay for when they go to a cinema and, this time, they didn’t. Despite the film bending over backwards in an attempt to please a semi-interested fanbase, Pacific Rim Uprising made almost fifty-percent less at the US box office and dipped by about twenty-five percent in the global market compared to the original’s take five years ago. (And that’s not taking inflation into account.) This is in spite of, or potentially because of, the film doing everything it can to appeal to a Chinese audience.

It’s a no-brainer as to why the film would do this. Even if it wasn’t the fastest growing film market in the world (that Hollywood is doing everything in its power to break into), the original Pacific Rim was one of the first big Hollywood films to make more money in China than it did in the US. Targeting it at China is the only way that the film, even hypothetically, makes financial sense. (Not to mention producers Legendary Pictures being acquired by China’s gargantuan Wanda Group.)

An overall lack of detail

A Pacific Rim sequel absolutely could have worked, in every sense, if it had focussed on the things that actually made Pacific Rim good. One of the best aspects of the original film, like with all of del Toro’s films, was the production design and the meticulous attention that del Toro pays to visual effects. Pacific Rim may not have been del Toro’s first time working with Hollywood, or CGI, but it was over double the budget of anything he had ever made before. And the finished film stands as one of modern Hollywood’s few, special effects heavy, behemoths that justifies its own price tag. It accurately reflects the level of quality and care that goes into the film. DeKnight was given a similarly sized budget and the quality is substantially inferior.

You could argue that it’s all DeKnight, the best parts of the film do definitely seem to be the ones that he, most likely, had the least involvement in. (The sound and the computer generated effects.)

Pacific Rim Uprising does mess up a lot of the stuff that the original hands it on a plate. It brings back Gorman and Day’s Gottlieb and Geiszler (quite rightly, as they were two of the best things in the first film) but fails to understand (despite the similarities in their very names) that they’re designed as a double act (they only really work as characters when they’re together) and it splits them up for the vast majority of the film.

It introduces you to a new fleet of Jaeger robots but they’re difficult to distinguish from one another. In the original, del Toro makes sure to get a wide shot on each of the Jaegers as its introduced. There’s only really four of them in the film (Gipsy Danger, Cherno Alpha, Crimson Typhoon and Striker Eureka). You get to know them and you get to know their pilots. They each have a unique overall design, and colour scheme, so it’s always clear where everyone is and what they’re doing in a fight sequence.

But, despite being set in a training academy where everyone works with these things all day, you never really get a good look at any of the new Jaegers in Pacific Rim Uprising. By the time the finale rolls around, it’s a struggle to remember which one is which and who’s piloting it. Not only are the designs worse, the names are even less memorable than del Toro’s originals. Bracer Phoenix, Valor Omega, Saber Athena, Titan Redeemer, November Ajax, Guardian Bravo - they just sound worse. There’s a certain level of incongruity to del Toro’s original names (made obvious by the conspicuously appropriate one, Crimson Typhoon) but all of the new ones just seem like what a six year-old would call their BMX.

As a character in the film grunts through gritted teeth during a standoff caused by one of the film’s many manufactured conflicts, which occur for no good reason and pretty much just resolve themselves, Pacific Rim Uprising‘s main mantra is: “Bigger is better.” Which, in filmmaking terms, essentially equates to: “More is more.” Which is a thing that nobody in filmmaking ever says because it’s abundantly obvious that it isn’t true.

Studio meddling

Alternatively, you can blame it all on the change of overseeing studio. The original Pacific Rim was made when Legendary Pictures were still working under their, quite lucrative, partnership with Warner Bros. But, just over a week after Pacific Rim premiered and two days before it opened in the US, it was officially announced that Legendary would be moving into the future under a new deal with Universal Pictures.

Universal and Warner Bros. are particularly interesting to compare as film producers, and distributors, because of a distinct difference that is no more prevalent than in the Pacific Rim films.

Four shots from four of Warner Bros’ highest grossing films of the past four years

Four shots from four of Universal’s highest grossing films of the past four years

For whatever reason (there are probably several) contemporary Warner Bros’ films are thought of as being, literally, very dark. They’re famous for having a low colour grading in their major films. (The DC comic book films are usually singled out as main offenders but it’s been quite a common practice for them since the Harry Potter films, at least.)

Universal, on the other hand have become recognisable for their high colour grading and extreme, almost aggressive and hypnotising, brightness. The net result being that most of Pacific Rim‘s outdoor scenes take place at night while most of Pacific Rim Uprising‘s outdoor scenes take place in very bright sunlight.

One of the chief rules of anime is that drawing a scene at night, especially in a city, is far more difficult than drawing a scene during the day. The darkness effects the colours and requires a much more complex palette but it can yield far more aesthetically pleasing results. (A good example of this is the opening scene from Katsuhiro Otomo’s 1988 film Akira.)

The visual end result of both films perfectly encapsulates their fundamental difference. Pacific Rim is a well-drawn anime and Pacific Rim Uprising is a cheap comic book. Pacific Rim‘s minutely detailed sets are replaced with bland, forgettable, backdrops, that could be from any number of science-fiction movies, and are smothered by an overabundance of, and over-reliance on, CG holograms that are designed to draw the eye away from the lack of detail in the vast majority of any given shot.

A severe lapse in quality

The CGI and practical elements, generally, don’t blend together very well in Pacific Rim Uprising. Again, in direct contrast to the seamlessness del Toro achieved in Pacific Rim. For reasons already mentioned, as well as numerous other ones, Pacific Rim Uprising is, all around, a poorly edited film. But it never feels quite as a jagged as when it’s splicing digital and practical together.

In Pacific Rim, del Toro gave the pilots full-face visors on their helmets. It was an aesthetic choice that couldn’t have been easy. (One of the chief things you have to worry about, when filming, is glare and reflection; especially when the surface in question is constantly moving and covering the actors’ entire faces.) But it pays off. It looks better and the controlled reflections on the visors assist the audience in emoting with the characters. They help us see what they see.

Pacific Rim Uprising just gets rid of them. The design, all around, looks worse and it actually makes far less practical sense. It’s weird to see someone standing in an armour that covers every inch of them except their face. Similarly, in del Toro’s original, the Jaegers had a certain tangible quality to them. Not just because of del Toro’s dedication to practical details but also because of the way in which they moved. It was an interaction between human and machine. They were slow and awkward compared to how an actual person would move and this gave them a distinct look.

In Pacific Rim Uprising, yes, the point is to show how time has passed since the last film and the Jaeger technology has advanced (even though they have nothing to fight and no real reason to be building them) but their movements become much more, uncannily, human. They move too easily and gracefully for what they are. They, physically, could not exist in our reality but del Toro kind of made you feel like his could.

There’s the crux of it. They’re both silly, enjoyable, films that you should never take too seriously (lest you miss the point of the whole experience) but one of them actually blends the fantastical into the real, it makes you engaged and excited and joyful. The other is fun to look at. But it’s not really any of those things. The brightness and the colour and the vitality and the comedy all feel like a distraction from the gaping holes in the film’s plot and overall level of quality.

Maybe Steven S. DeKnight has an incredibly unique voice, that has as much to say as a feature film director than Guillermo del Toro. You just wouldn’t know it from his directorial debut. The odd couple pairing of Boyega and Eastwood, which is what was initially sold as the heart of the film, could have been enough. But Pacific Rim Uprising is always adding more rather than just working with what it has. Bigger isn’t always better.

Pacific Rim Uprising is out now on Blu-ray and DVD in the US and will be available in the UK on July 30th.