We take a look at the extreme reactions to Duncan Jones’ new Netflix sci-fi noir Mute and what they mean for the relationship between critics, creators and audiences.

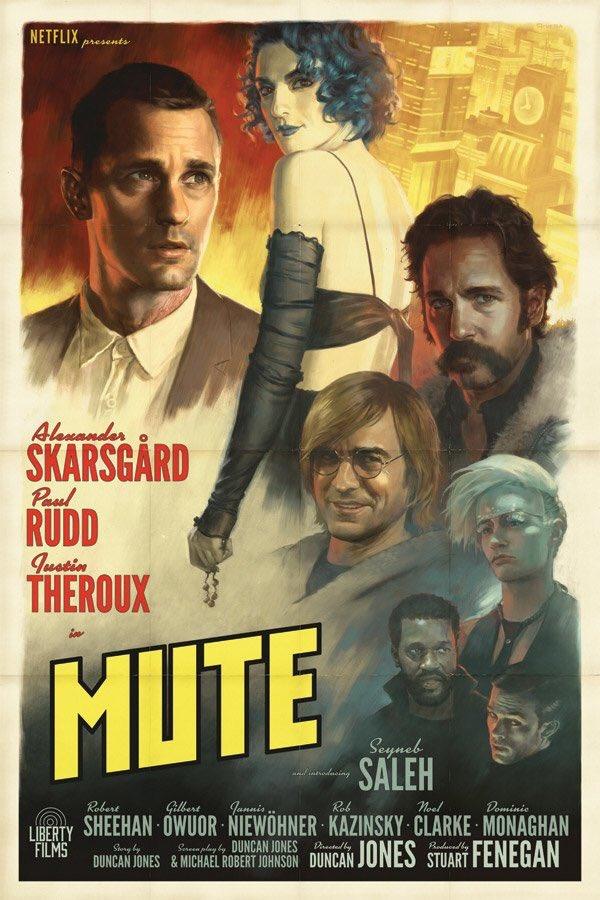

Another day, another Netflix cataclysm. Duncan Jones’ hotly anticipated, Blade Runner-esque, science-fiction film Mute became available for all users of the service to view the other day and all of those factors appear to have worked both for and against the film in equal measure.

Jones has been a closely watched director due to his extremely strong feature debut Moon in 2009 (to which Mute bears a connection) and also, inescapably, his parentage. (Jones is the son of late music icon David Bowie; to whom the film is dedicated, as well as his nanny Marion Skene.) Expectations surrounding it appeared to be abnormally high for such a production. This is also because Mute falls into the fascinating, and ever encroaching, grey area of film criticism today where it becomes difficult to assess whether or not it actually is a film.

Netflix productions are rarely released in actual cinemas for public consumption, causing them to fall more in line with straight-to-video standards and practices whilst simultaneously being of a far higher production value than that classification would allow. (But still not really being close to the level of quality that a general filmgoer would consider to be acceptable from a studio-funded, wide release, feature film.) Blade Runner 2049, to which this film will be almost constantly compared by essentially everyone for a number of reasons, is a very good example of a film which lived up to these cinematic standards and Mute proves to be a considerably worse film when compared against the things which Blade Runner 2049 got right. It also, however, proves to be a success when compared against the things that Blade Runner 2049 got not as right.

Blade Runner 2049 is a very good film but its key strengths lie in the most ostensible qualities of a modern Hollywood studio film (cinematography, music, special effects) and less in unique characters, situations or even ideas. Things which Mute excels at thanks to some odd, but rewarding, casting choices and uncomfortable themes.

Unlike Blade Runner 2049 and the other science-fiction films of 2017, Mute moves beyond the idea of creation to what it means to be a parent. (You may have noticed that Jones dedicated the film to his biological father but not to his biological mother under the banner of “people who became parents.”) The film also deals with not only abuse and paedophilia but also people’s reactions to them. It’s very provocative and provocativeness has proven to be not much more than an immense burden when weighing a film’s success against its critical score. Something that can be, and is, measured in minute, and often misleading, detail in today’s climate.

People’s reactions to films have always taken precedence, in the media in general, over analysis of the actual film because opinion is simply an easier sell than critical analysis; which offers vaguer, and more ambiguous, conclusions opposed to the clear definition of an immediate emotional response. Film criticism is also a growing industry within itself. With the slow death of print and the rise of online news sources, film critics have become increasingly less associated with middle-aged academics and journalists (who have worked their way up to a position within a reputable, or at least established, newspaper) and more with the “film school rejects” and “screen junkies” (both actual names of widely used websites that shape the discourse around film today) generation. This has contributed to an explosion in film culture over the past decade alone. Meaning that films can achieve huge success provided that they ride the wave of that culture and don’t rock the boat.

The problem being that the explosion in film culture may just, realistically, be in line with the rise in population and all of its changes have not made it any less insular. In fact, they may have made it more so.

Critical consensus is a topic which is continually coming up in our conversations about film today and it’s likely to only become more and more frequent over the next few years. It’s important to bear in mind that all of the changes made to our access to film, and film criticism, are not done altruistically. Perhaps now more than ever, film criticism is a viable career for people who wish to be a part of the film community. It is a job, and jobs have cultures of their own.

Film critics have also developed a reputation, over the past five years or so particularly, for clamming up very defensively and unanimously when accused of groupthink or favouritism. If it’s your job and you spend most of your time doing it, and socialising with other people who do it, then would it not be an absolutely ridiculous claim that you aren’t influenced by the opinions of your peers and the prevailing mood within that circle? The larger that circle becomes then the greater the likelihood that it will inevitably begin to feed on itself.

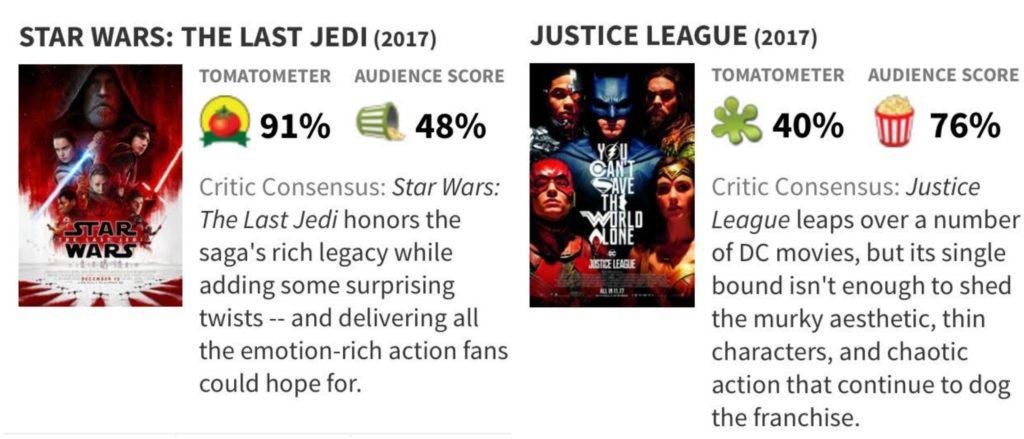

Concurrence between critics and the public is becoming progressively more and more rare with the biggest films on release.

A lot of people believe that this results in film criticism becoming not just overly political but mired in a liberal mindset. Generally, I’ve found this to be untrue and that films that do the best within the current climate tend to be the most apolitical or even conservative. Essentially, the films that do the best are the ones which stick most closely to the current status quo.

The more a film provokes its audience (a lot of whom will have blogs or YouTube channels of their own, which they are capable of making money off of) the more likely it is to garner a response which takes time and a level-head to properly break down and explain. If the film offers, if nothing else, basic success in the fundamentals of filmmaking and a story that appeals to popular public sentiments, while not going beyond them and into the realm of the taboo or challenging, then it is essentially guaranteed a large number of positive reviews. Which accounts for the increasing number of mediocre, or average, films which receive overwhelming, and seemingly disproportionate, critical praise and support whilst smaller films, outside of mainstream discourse, can still receive high praise from a smaller number of critics without it impacting that film’s distribution or success in the market.

Bearing all of this in mind, Mute is a weird hill to die on because it’s not a particularly great film. But the conversation about online films, and how they’re received by critics (who do, in all their many forms, still influence what people watch), is still one that needs to be had. And it stands as the most recent in a consistent string of uproariously controversial films that Netflix has put out in the past few months as part of a new phase of high-end production.

To some extent, this phase was always going to cause this response from critics at large. Film critics, as a homogenous brand, focus mostly on wide releases. If your film plays in a multiplex, or a chain of independent cinemas (if that’s not a contradiction in terms), it’s essentially guaranteed a review and it carries with it a sense of legitimacy as a result. Netflix almost entirely circumvents this process, delegitimizing the critic. This usually doesn’t make them happy.

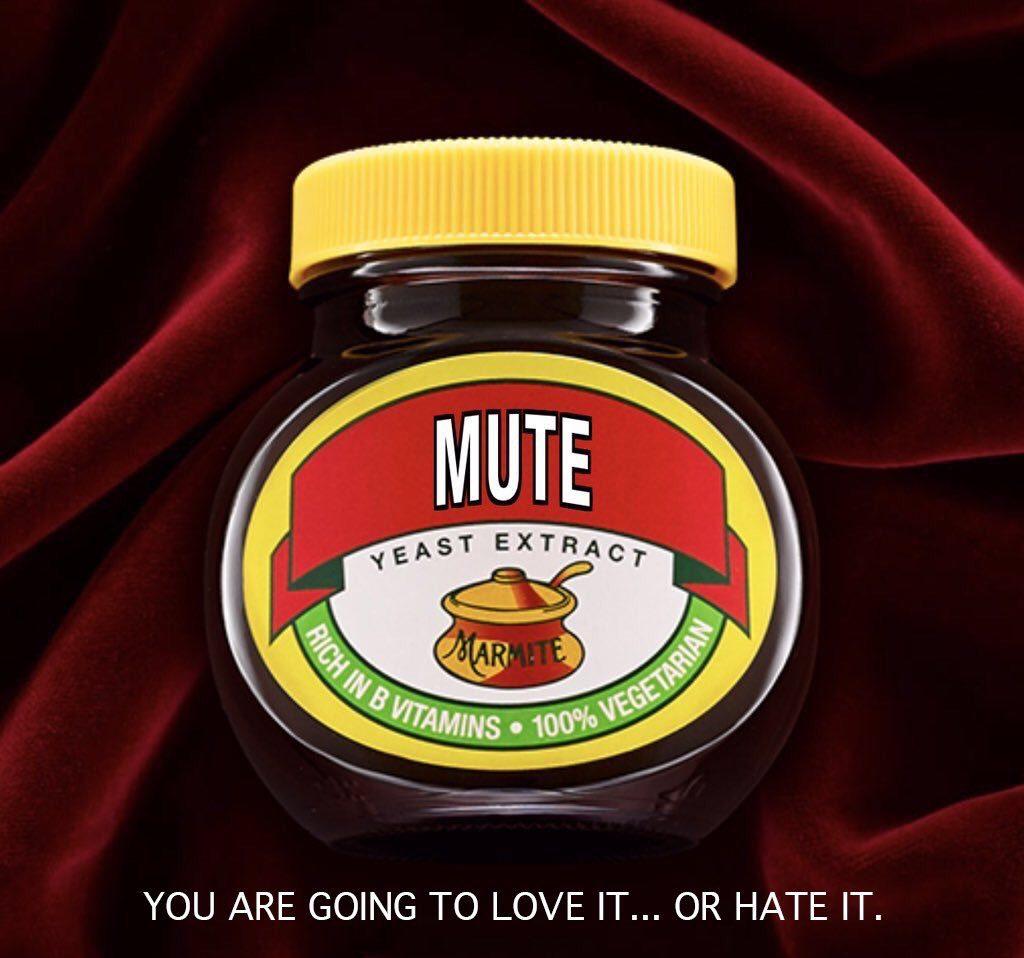

An image tweeted out by director and co-writer Duncan Jones prior to the film’s release.

I’m not arguing for the death of cinema, no reasonable cinephile ever would. But a hard truth, that film-lovers the world over are steadily coming to grips with, is that the theatres have become overrun with workaday “franchise” films; which play very well into the hands of modern criticism, with their nostalgia and general appeal, and place value on brands above artists. Mute, whilst a failure in many respects, fails and succeeds on decisions made by individuals and not a boardroom committee. Thus, it will play as a success or a failure within the minds of individuals and not a clearly defined group which increasingly appears to have a party line to toe.

A common criticism of the film found in legitimate publications is that it is “tone-deaf”, implying that the film is unaware that there is a list of topics that must be discussed in a certain way because that is what the status quo demands. If this doesn’t sound completely antithetical to the nature of artistic expression to you then, if you haven’t figured it out by this point, you and I probably aren’t going to agree on a lot.

With not just the immediacy of the film’s availability but the narrow window in which it is the most profitable to put out content regarding a certain topic, film reviews are increasingly an immediate response (in internet and social media terms, a reaction video) rather than a thought-out critique. Meaning that the divide between the public and critics is no longer really a disconnect between the knowing and the unknowing but rather a disagreement between people who either do, or do not, see what they consider to be acceptable ideas which conform to pre-existing beliefs.

For example, one of the things that people have taken umbrage with is a scene in which a paedophile is outed to his friend before the friend immediately forgives them and embarks on an over-the-top shopping spree with them. Surprisingly few people appear to have assessed the scene and its meaning. (The friend who glosses over the paedophilia and ultimately does nothing, despite verbal threats, is the villain of the film and is characterised by his motor mouth; whereas the hero of the film, who is mute, takes the only absolute moral stances of the film.)

Mostly, the reaction has been that the scene and the theme should not exist in the film at all and that it acts as a condonement of sexual assault. The behaviour itself, not the reasoning behind it, is deemed to be absolutely unacceptable. Creating rules like this is a helpful crutch to anyone who has to see multiple films a week, or day, for a living and they’re also one of the chief causes behind an era of films that have figured out how to game the system. Following your own set of internal rules, like that of the fictional world within Mute or the noir detective genre to which it sticks so devoutly, often results in the film’s ethos running in opposition to the critics’.

One of the most interesting things about Mute, and Netflix films in general, is that because Netflix is still a burgeoning content creator, especially in the field of feature films, they are either not yet willing, or not yet capable, of leaving huge amounts of finished footage on the cutting room floor. This means that, for better or worse, films like Mute hand authority back to the creators and not the people who own the trademarks. And that’s the thing, it’s always going to be for both better and worse. There are always going to be mistakes when you’re breaking free from the status quo. There is always going to be an element of risk if you’re going for something which, at the very least, attempts to be new.

Mute isn’t a sequel despite its connection to Jones’ first film and it hides its biggest stars behind impenetrable makeup, ridiculous facial hair, truly repulsive characters and utter silence. It is, for better and for worse, daring. It plays like an overly-ambitious sci-fi film that would have been taken away and butchered by any Hollywood studio; only to be slowly and painfully reconstructed over a period of decades. But, instead, was simply just released, warts and all, as the director intended. Not everything is about gratification, nor should it ever be.

Jones himself tweeted out a picture of a jar of Marmite bearing the film’s title on the eve of its release (with the caption reading: “You are going to love it… or hate it”) and it’s proven to be very correct by responses within the first twenty-four hours alone.

In the state of modern film criticism, headlines competing for attention within the algorithms of Search Engine Optimization and our ever decreasing attention spans, hyperbole thrives amongst a constant flippancy towards anything that offends us. We, funnily enough, just mute what doesn’t immediately meet our standards. Mute is a difficult, awkward, and frequently rewarding film for those who love the genres of noir and neo-noir and its immediate, and total, rejection by so many publications, so quickly, serves as a sad reminder that if all a critic delivers to their audience these days is a simple human reaction, based on what’s popular, then what use are they? Make up your own mind, not just because you should anyway but because it looks like you have to.

Mute is available to view now on Netflix.