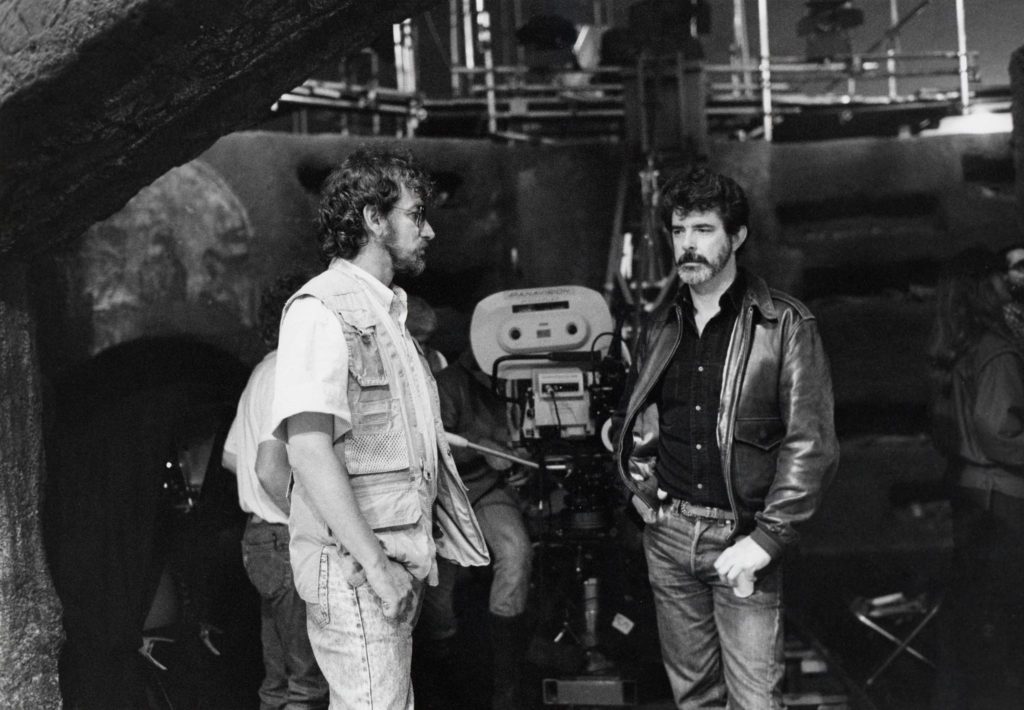

John Higgins goes back over the innovations produced by one of the most prolific bonds in the history of cinema: the Lucas and Spielberg friendship.

Their work continues to pioneer and influence umpteen modern filmmakers and they retain that ever-friendly rivalry, going back to their early days at the inception of the so-called ‘Movie Brat’ generation.

Whilst Steven Spielberg has gained critical acclaim and awards for films like Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan, George Lucas’ autonomous mind-set, which prompted him to relocate to Northern California after the release of Star Wars (highlighted by well-told problems with the studio during the making of the film at Elstree Studios) enabled him to pioneer numerous concepts and technical developments that have not only brought him tremendous wealth and artistic satisfaction in a way (heightened of course by the multi-billion dollar sale of his parent company Lucasfilm to Disney in 2012), but improved and increased the stock of his good friend Spielberg.

The two film-makers are entwined into film history. Future classics Jaws and Star Wars were made amidst intense pressure and technical set-backs (particularly with the shark in Jaws not performing at times, but solved thanks to Spielberg’s skill, coupled with editor Verna Fields and John Williams’ effective orchestral simplicity), but from Raiders of the Lost Ark in 1981 (conceived over a sandcastle on a beach in Hawaii in May 1977, so the legend goes) the pair helped shape the cinema-going experience; in particular Lucas, who had already envisioned a more digital-friendly film-making environment.

Lucas’ filmography might have paled into insignificance compared to the volume of artistic and financial success Spielberg has had, but there isn’t a major player in film directing who has not benefitted from the templates of technology Lucas has put together. Pixar’s recent success in cinema stemmed from the foundation laid in the late 1970’s by Lucasfilm’s own computer division, whilst Skywalker Sound is a brand-name that can be glimpsed on many of the end credits of blockbusters today. Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) has spawned two other key contributors in FX with James Cameron’s Digital Domain and Peter Jackson’s Weta Workshop, which Jackson admitted in the preface to JW Rinzler’s The Making of Star Wars had been created as a direct influence of ILM.

One also wonders how well-received Spielberg’s films would have been, if they didn’t have the artistic qualities of production design and FX that had been pioneered by ILM. The Star Wars prequels were made possible as a direct result of experimental film-making ideals utilised on Lucas’ Young Indiana Jones series and, of course, the tweaks made to the Special Editions of the ‘Original Trilogy’.

Looking two decades on from the release of those Special Editions, there are questionable issues with some of them – personally, it’s a shame they didn’t include some of the early Anchorhead footage and Tosche Station sequences (the meeting with Biggs in the hangar before the Death Star battle doesn’t make as much sense to the unaware if you haven’t read the novelization of A New Hope (credited to Lucas, but ghost-written by veteran writer Alan Dean Foster). Star Wars is the most improved because of the CGI additions (especially in the Death Star climax) but, even at the time of their original productions, Empire and Jedi were already pushing the boundaries of the effects at the time, with those legendary sequences in the Asteroid Field and on the Forest Moon of Endor.

The ‘Greedo shot first’ controversy reigns today and fans do yearn for the original versions of the films to be released on Blu-Ray. (That said, if you toy with your HD TVs and try and get hold of the Bonus DVD disc of the trilogy which was available for a short time a few years back, you might get something that’s close to it – I have held onto my copies!)

For all the criticism levelled at those Star Wars prequels (which affected the careers of Jake Lloyd and Hayden Cristensen in the aftermath of their appearances as the boy and young adult Anakin), it was pointed out in an edition of The Star Wars Insider Magazine that the reboot mind-set of the likes of Bond, Batman and Marvel might not have happened without the success of those prequels. Whilst Jar Jar Binks remains in some circles the most annoying alien and film character in recent history, some would be naïve to ignore the character being a template for the more regarded and acclaimed Andy Serkis portrayal of Gollum in the Lord of the Rings trilogy. The likes of the Marvel updates and Guardians of the Galaxy have certainly benefitted from the ILM foundations.

Who hasn’t seen a THX-mastered soundtrack on a movie in recent years? Spielberg, Cameron, Jackson and Marvel have all had the endorsement and many other films like Braveheart have had it as part of their Home video release. If you were an attendee at theatres and were willing to stay the course of the end credits, you would have seen a credit for the THX TAP (Theatre Alignment Programme) on films like Independence Day.

Spielberg always remains loyal to Lucas when it comes to post-production, with the likes of ILM and Skywalker. Jurassic Park became a reality through the test footage of the CGI rendered dinosaurs which wowed Spielberg in pre-production over Phil Tippett’s stop-motion techniques (although Tippett became part of the team after working on earlier Lucas productions) and there doesn’t seem to be a film today in the blockbuster realm that doesn’t have some kind of CGI-enhancement. It even applies to smaller productions like The King’s Speech and many others, who utilise backdrops to expand the period look of films. Peter Jackson’s King Kong remake in 2005 used a computer program to recreate the New York City of the 1930s – the period captured in the original Merian C. Cooper 1933 classic.

Literature has also become a cinematic possibility with films like the Harry Potter franchise, The Jungle Book and Tolkien becoming more incredibly realised with the recent version of the Kipling classic garnering incredible acclaim. Films like The Legend of Tarzan didn’t need to be shot on location (with back plates shot in the Gabon, but the majority of the film shot on soundstages in Watford, England).

One suspects that Spielberg yearns to do another Lawrence of Arabia type epic before he retires in honour of his idol, the late Sir David Lean – and you can guarantee Lucas’ legacy will be there to help realize it. Lucas’ philosophy now with the advent of those technological advances is ‘if you can write it, you can film it’ makes anything possible.