A presentation of Brad Bird’s Tomorrowland as a masterclass in how a film’s intended themes can become completely inverted.

One of the most irritating things about the recent deluge of remakes and reboots and sequels is that people do actually make these much sought-after, original concept, sci-fi films; more often than not, though, they tend to be flawed beyond the point of genuine enjoyment, at least to a general audience member. It doesn’t make them worthless, far from it, you have to break a few eggs if you’re going to make an omelette; and Tomorrowland is most definitely a broken egg.

Its colossal box office bombing resulted in Disney making a public show of scaling back on their original sci-fi scripts, heralding the death of several projects (most notably the belated third Tron film) and it’s easy to see why it failed to connect with its target audience. Which is, primarily, because that audience did not exist. It was far too cutesy for adults and far too boring for kids, its biggest stars were in their mid-50s, its action is plentiful but not engaging, its point didn’t even begin to rear its head until the final 20 minutes of its two hour runtime and, whether the audience had the sense or energy left in them to know it, it is this point that is Tomorrowland’s most irksome quality.

As the film’s climax finally kicks into gear, and the intricacies of Hugh Laurie’s underwhelming villain are revealed, the audience finally becomes beaten over the head by the film’s overarching meaning one final time, which is: optimism is better than pessimism. As an idea, it’s neither that original or that irritating. The problem it creates within the film’s story is just how antithetical that is to the direction in which you believe it wants to go. Tomorrowland is, inherently, a film about invention and is, inescapably, a product of its inventor; director and co-writer Brad Bird.

Despite persistent allegations that Bird’s work as an animation director was informed largely by a belief in Ayn Rand’s Objectivist theories (which Bird has called “lazy and inaccurate at best”), he’s a typically outspoken classical centrist Hollywood liberal. There’s nothing wrong with that and there’s nothing wrong with it impacting his work (it’s his work) but the knowledge of this serves to highlight the film’s most fatal flaw beyond even its remarkably clunky pacing. Tomorrowland is, deep down, one of the most absurdly tone deaf Hollywood films of recent years.

There are the more cosmetic problems, like having the main romantic thread of the film run between a fifty-five-year-old man and a thirteen-year-old girl, but what we’re dealing with here is the more fundamental cracks within the very ethos of the film. In the finale, the story’s mysterious cause of conflict is revealed to be “the monitor”, a thinly veiled metaphor for late-twentieth century advancements in telecommunications (for the sake of argument, let’s say: television) particularly within the United States. It goes on to draw parallels between post-apocalyptic visions of the world and a general state of apathy in society towards serious problems which have manifested themselves as some nondescript environmental cataclysm.

Setting aside how irritating that is to anyone who has enjoyed these apocalyptic fantasy dramas, in any of their forms, over the past decade or so, exploding in popularity again thanks to the financial crash and their correlating core aesthetic of attempting to find hope in a hopeless situation, there’s something that’s just off about Tomorrowland’s overall message. Because it’s ultimately about hope as well but, unlike post-apocalyptic science-fiction, it’s not about making tough choices and learning to accept the things that cannot be changed in life; it’s about reshaping destiny and the future by force. Once you realise this, it’s where the film starts to get troubling.

As a vision of modern day America, and even the America of fifty years ago, Tomorrowland is astoundingly white. Keegan Michael-Key, in fact, plays the only named, non-white, character with a speaking role in the film. It’s fairly clear that Tomorrowland was gunning to be part of the 2015 resurgence in the “the future is female” slogan which had bounced back into popular culture amid the resurgence of feminism in centre-left American politics and became heavily linked to Hillary Clinton’s long-anticipated 2016 run for president of the United States (Clinton quoted the slogan in her first public appearance in the wake of her loss to Donald Trump), which was officially announced one month prior to Tomorrowland’s release. The film even goes so far as to have the character of Athena announce herself as “the future”.

A huge part of that political conversation centred around the drive to increase the number of women in so-called STEM fields, particularly by way of media representation. It’s a conversation that’s still ongoing but Tomorrowland is fairly demonstrative of the kind of quick fix solution that Hollywood would attempt to throw at the problem, often resulting in vague, and meaningless, pseudoscience being attributed to characters who never feel, or behave, like actual scientists nor earn the level of dexterity which they’re given by their screenwriters.

Tomorrowland would really exemplify this with its protagonist, Casey Newton, whose miraculous abilities would be simply, and immediately, explained away by saying that she “just knows how things work” but one of the biggest, and most long-lasting, debates on the subject would centre around Daisy Ridley’s protagonist, Rey, in Disney’s Star Wars: The Force Awakens later that year. Tomorrowland obviously being a segue into that overall ethos at Disney, with various visual references throughout the film which include a scene where characters are literally smashed in the face with models of R2-D2 and the Millennium Falcon.

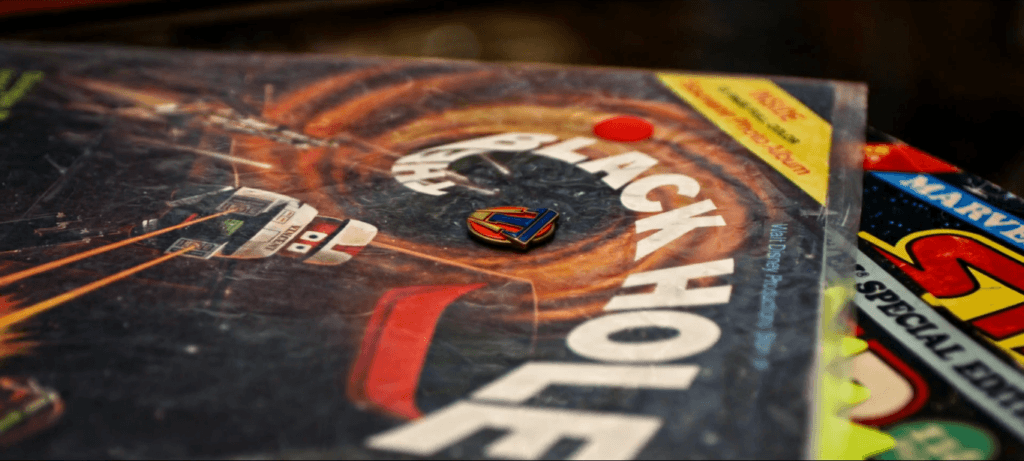

Keeping with the tradition of Disney’s unofficial sci-fi department, The Black Hole makes an appearance also

The vision stands for optimism towards a specific idea of utopia in the face of all the overriding evidence; a return to the giddiness of the Space Age. As Bird put it, “When [co-writer Damon Lindelof and I] were little, people had a very positive idea about the future, even though there were bad things going on in the world. Even the 1964 World’s Fair happened during the Cold War. But there was a sense we could overcome them. And yet now we act like we’re passengers on a bus with no say in where it’s going, with no realisation that we collectively write the future every day and can make it so much better than it otherwise would be”.

I think Wired’s Adam Rogers put it best when he wrote, in response to Tomorrowland’s early promotional footage in the run-up to the film’s release: “The problem with world’s fairs isn’t that the vision of the future they sold didn’t come true; the problem is that it did.” Much like political sentiment at that time, which failed to win over a vast majority of the electorate, Tomorrowland does accept the past as a cause of today’s ills but offers nothing in the way of a replacement. Rather, it offers a rebranding of the same ideas under a new banner.

The troubling aspect of this, the unbearable irony (as it were), is that Tomorrowland did turn out to be a prophetic piece of political cinema; but not for Hillary Clinton or any of the social causes associated with her. A lot of Americans did take Tomorrowland’s advice, they stopped trusting mainstream media’s vision of an inevitable future, they started to rally behind a defiantly optimistic counter-vision inspired by post-World War II industrialism, and consumerism, which fuelled white suburban middle class growth. They elected Donald Trump as president of the United States, a vehement climate change denier who has since moved the United States, and the world therefore, closer to the film’s vision of an apocalyptic environmental disaster.

George Clooney’s wizened 60s optimist brings Casey to Tomorrowland to “fix it”; “it” being “the world”, or as much of the world that Tomorrowland can see (which is America). In essence, her job is to make America great again. The film becomes less and less about creating a new future and more and more about repurposing the past. Overseen by the architect of Tomorrowland’s biggest mistake, Casey founds a new meritocracy (where the selected ubermensches are literally awarded special badges) filled with people who seem to have no other qualifications for a role in scientific research than being able to play the guitar. It becomes hard not to think about the vastly unqualified candidates the Trump administration has placed into administerial, and judicial, roles in an effort to drastically shake things up.

I think Brad Bird is quite an intelligent filmmaker; or, at the very least, an emotionally intelligent filmmaker. The same going for Damon Lindelof. I, however, don’t think they’re clever, or rebellious, enough to produce this deeply ironic film on purpose. An Atlas Shrugged inspired sci-fi nightmare world where the protagonist witnesses a system built on extreme divisions in opportunity and wealth, a literal Galt’s Gulch, only to then want to become the ruler of it.

Clooney’s Frank Walker talks about a proposed golden era where Tomorrowland would become opened up for everyone, he gains control at the end of the film but that moment never comes. It’s just the mistakes of the past, repackaged for the latest generation. The simple truth of this film is that it so blatantly wants to stand as a shining example of Walt Disney’s optimistic persona and his company’s upbeat brand but what Bird really made was a film that exposes the darkest roots of what the white middle class perceive to be America and its legacy.

As Charlie Jane Anders puts it, in her review, “nostalgia for optimism isn’t optimism”. In a film that should be all about innovation and original thought, instead we have a passionate battlecry for going backwards. Revelling in old ideas, old concepts, and literally working to rebuild the ruins of a failed state. Much like old man Disney himself, the futurist design style, itself, has as many inextricable links to racism as Ayn Rand’s works. (It’s interesting that the only named black character with a speaking role is named after “father of science-fiction” Hugo Gernsback as the annual sci-fi and fantasy literary awards which were named after him, the Hugos, were famously hijacked by right wing conservative factions only a month prior to the film’s release.)

I’m not really suggesting that Tomorrowland in any way caused Donald Trump’s election as president of the United States because, aside from anything else, that would be to afford the film far too much credit. But it is a very useful tool for understanding the mindset that some affluent people in America had during the time running up to the political climate of 2016.

Like the one which producers used to originally advertise the film [pictured above], it really is like a time capsule. From an era where people could genuinely, innocently, create a supergroup of master race scientists, founded entirely by rich old white men, called Plus Ultra (there’s a name for a skinhead terrorist cell if I’ve ever heard one) and just not see the problem. In a lot of ways, I’ve found Clooney’s 2017 writing/directorial effort Suburbicon to be part way a reaction/apology to Tomorrowland’s treatment of race and nostalgia for the purity of post-war optimism and I’d recommend it as a way of finding some kind of balance. Because this isn’t an overly stupid film, and it’s clearly made by intelligent people, it just ended up making its audience engage with its themes in ways it probably didn’t intend to. Putting it in the category of “accidentally relevant”.