Maverick. Poet. Crusader. Goon. Lynsey Ford discusses the life and career of the revolutionary actor and comedian Spike Milligan.

Spike Milligan | Courtesy of The British Film Institute

On May 7th, BFI Southbank will celebrate the centenary of Spike Milligan’s birth with Spike Milligan Day, releasing rare archive footage charting Spike’s transition as a pioneer of post-war Radio Comedy through to his leading roles in television and the silver screen.

Spike’s anarchic brand of humour influenced a whole new generation of alternative comedians from Monty Python to the late Robin Williams and Eddie Izzard. For BFI Curator Dick Fiddy, who is programming the special one-off event, ‘He was undoubtedly ‘The Godfather’ of comedy. Spike’s humour was mostly shaped by the war viewed through his innate form of Irish whimsy.’

Born in Ahmednagar in 1918 to Irish Captain Leo Alphonso Milligan and English housewife Florence Mary Winifred, Spike was raised in India and Burma by Irish Catholics and nuns. Terence ‘Spike’ Milligan quickly developed, as daughter Jane recalls, ’a vivid imagination. To quote Spike ‘my father had a profound influence on me, he was a lunatic! Spike was a big fan of films (he loved the screwball comedy of The Marx Brothers) and was a voracious reader; his imagination was like nothing I have ever come across.’

Rising to the ranks in The British Army as Lance Bombardier in The Royal Artillery Regiment during World War II, Spike suffered shell shock and a mortar wound to the right leg at The Battle of Monte Cassino in Italy. Honing his natural musical talent with The Bill Hall Trio with the troops as drummer, crooner and guitarist, Spike would later develop his musical skills upon his return from the war in the UK playing the ukulele, and jazz trumpet in various establishments.

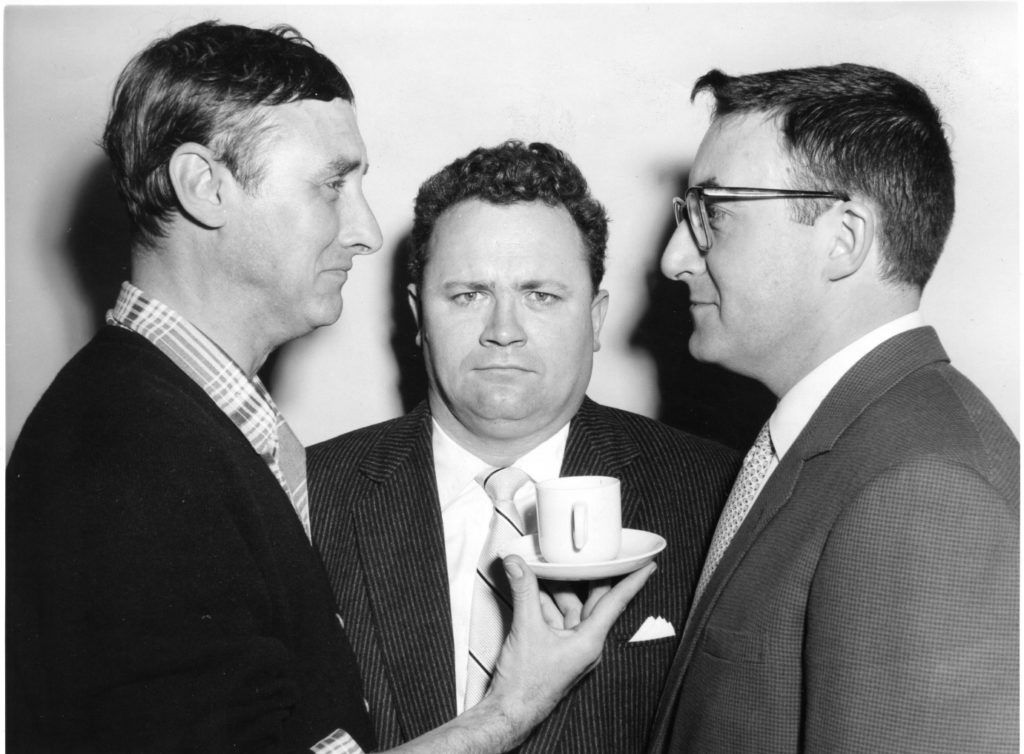

But it was his through his natural gift for comedy that he revolutionised post-war radio through his scripts for the BBC Home Service in May 1951 as part of The Goon Show (initially titled Crazy People). Spike, as principal writer, joined up with performers Peter Sellers, Michael Bentine and Harry Secombe, introducing an immersive secret underworld run by assorted (but endearing) misfits including Eccles, Count Moriarty and Minnie Bannister, all vividly brought to life with adlibbing and complex electronic effects from the BBC Radiophone Service.

The Goon Show | Courtesy of The British Film Institute

Spike’s creative drive and pursuit for excellence was at the detriment to his own health, emotionally overwhelmed by the relentless pressure to deliver twenty-six shows a year (across nine years) for The Goon Show. It was, concedes Jane, ‘extremely intense, and deadlines were hard. He had a vision in his head but was up against negativity and authority at the BBC, with Spike fighting to get the quality and support he needed to get aspects of his show right. Spike was more involved in the technical aspects, he was an extreme perfectionist. Spike was also raising three small kids alone for some of the time, whilst suffering depression and PTSD from his war experiences.’

Spike recognised a kindred spirit in fellow Goon Peter Sellers, who he first encountered in 1946 at The Grafton Arms, in Westminster where Sellers was developing his act as an impressionist. Sellers, according to Dick, demonstrated ‘almost supernatural ability to create characters vocally, which was the perfect complement to Milligan’s madcap, scatological universe of The Goons. Spike created a new kind of surreal comedy, dragging radio comedy from the Music Hall into a more modern era.’ Dick admires Spike’s creativity of ideas, ‘Some of the best moments from The Goons include the plan to climb Everest from the inside, and their idea of a ‘prison brake’ to stop a runaway jail. Surreal humour does age better than most forms of comedy; we know from the enduring appeal of silent film comedy that slapstick can be timeless and The Goons were aural slapstick.’

Spike and Peter branched out into film, starring in The Running, Jumping, Standing Still Film (1959) directed by Richard Lester. Nominated for an Academy Award as a 12-minute short featurette, they made the film over two Sundays ‘It’s on the cusp of comedy and experimental cinema, with a visual style that mirrors the audio craziness of The Goon Show, says Dick, ’The film harks back to the special effects (jump cuts, speeded up motion) of early experimental ‘gimmick’ films but allied to a modern surrealist take. Richard later incorporated this innovative style of film making on the A Hard Day’s Night. Later that same style was utilised on the US Monkees TV series, creating hybrid pop music/comedy.’

The Goon Show | Courtesy of The British Film Institute

Jane explains the strong chemistry between Spike and Peter Sellers who were united by ‘a bond of love and respect, success, humour, music and family. They were both wonderful clowns, and their meetings were always a total frenzy of gags and laughter between them both. They were big fans of the latest technology, and both had state of the art cameras, bringing about ideas that always flowed quickly.’

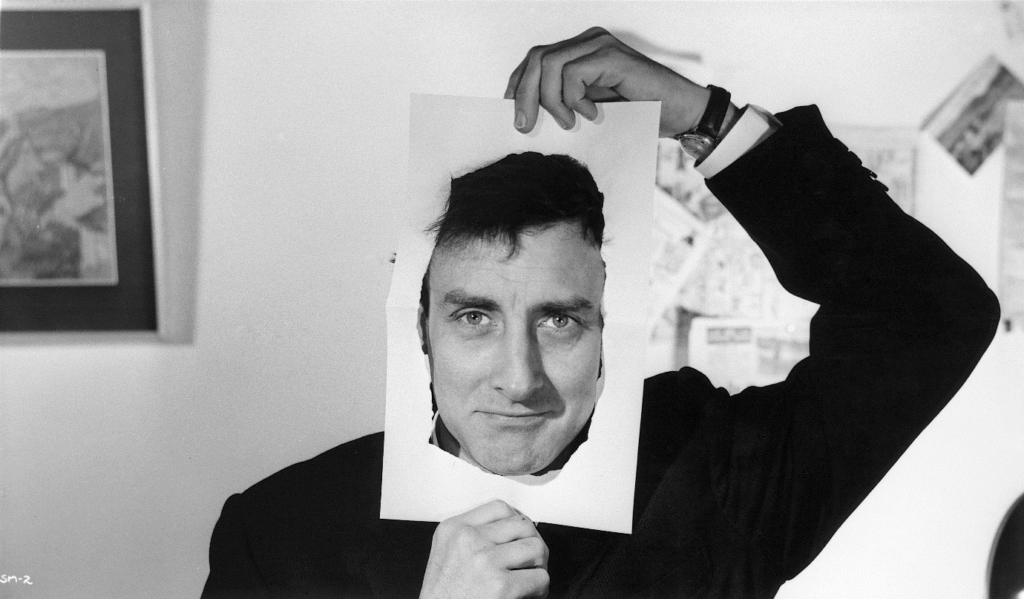

After The Goons officially ended their radio broadcasts in 1960, Spike took on the role of leading man in Postman’s Knock (1961). Designed as a vehicle to showcase Spike’s talents on the big screen, Dick admits that the film’s appeal is subjective, but ‘It is interesting to see him try and fit into a more mainstream and comedic style. It rarely gets screened in a cinema, and often seeing a film on the big screen can change your perception, and make you want to re-evaluate it.’

Postman’s Knock | Courtesy of The British Film Institute

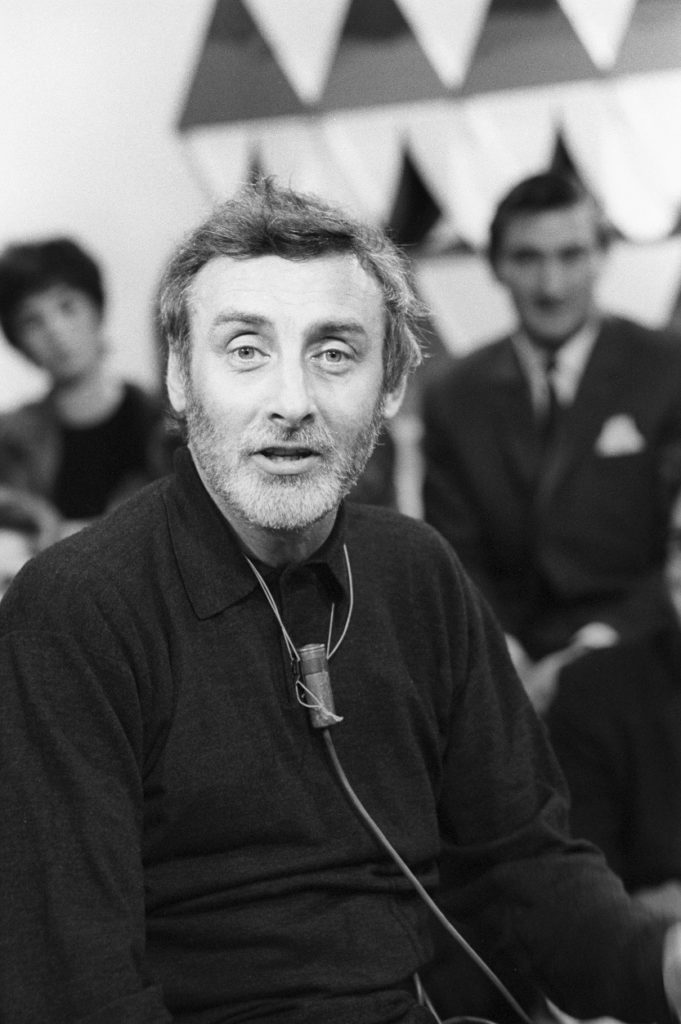

Norma Farnes was Spike’s PA, Manager and closest friend from 1966 until his death in 2002. Answering an advert for a ‘PA to a Showbiz personality’, Norma speaks of Spike with love and affection as one who introduced a new form of alternative comedy, someone who was ‘eccentric, totally illogical, but compassionate, with flights of fancy’. Their partnership endured great ups and downs, but they made a formidable team, held together by their mutual ‘respect for each other. He was driven, with great discipline and dedication; the most compassionate man – he wanted to save the World. He was ‘a piece of gold’. But the other Spike would say ‘I’ve served my apprenticeship, tell the publishers it’s all off! I would stick a note under his door when he was feeling sheer despair, when he was shouting at the World, when he felt the need to lock the door and self-medicate. I would leave him for a day or two – he’d ask me ‘why are you keeping me unemployed?!’. As Spike once said, ‘Van Gogh couldn’t stop painting, and I can’t stop writing.’ Norma and Spike would share offices in Orme Court, Bayswater with the crème de la crème of British comedy talent including Frankie Howerd, Galton & Simpson and Spike’s Best Friend and co-writer Eric Sykes, who all had the unenviable task of writing comedy scripts on Thursday ready for filming the following Sunday.

Spike Milligan | Courtesy of The British Film Institute

Widely lauded as a poet, Spike also released several books of poetry dedicated to his young children (notably Silly Verse For Children & A Book of Milliganimals) for Sean, Silé, Laura and (later) Jane, whom he adored, and would often leave miniature notes hidden in the garden for his children to find, which were (officially) left by the ‘fairies’. Looking back on her relationship with her dad, Jane remembers the lessons she learned from Spike, who advised her, as a daughter and actress, ‘To work hard, avoid idiots, and not to trust the contract until it is signed. Spike was devoted to his kids; he constantly inspired me to be creative, his pride knew no bounds and neither did his capacity to love.’

For Norma, her own favourite Spike poems include ‘The New Rose’:

The new rose

trembles with early beauty

The babe sees the beckoning carmine

the tiny hand

clutches the cruel stem

The babe screams

The rose is silent

Life is already telling lies.

Another favourite for Norma is ‘Small Dreams of a Scorpion’ (with illustrations by his daughter, Laura) which demonstrated Spike’s ‘emotional depth, vulnerability and raw candour’ touching on painful autobiographical aspects including clinical depression. It is therefore, ironic for all his poetic brilliance and diversity as an artist that Spike would play the lead role in Joseph McGrath’s feature The Great McGonagall (1974) playing (real-life) Victorian ‘poet’ William Topaz McGonagall, infamously known as ‘The World’s Worst Poet’, feebly attempting to appease the dour Queen Victoria (Sellers). The production, co-written by Spike with McGrath was highly unusual, taking only three weeks to make, with Peter completing filming in just one week. Dick Fiddy acknowledges the difficulties in performing across different mediums: ‘On radio the team were pretty autonomous with the protagonists completely on-board with Spike’s vision. With film the power is dissipated and its harder for one person to completely realise their ambitions. Films by the very nature offer a compromise and that had a telling effect on the teams attempts to bring the ‘Goon’ style to celluloid.’

Spike literary career nevertheless continued to flourish with the publication of seven volumes of autobiographical war memoirs, and it was in Spike’s adoptive country of Australia where his parents and brother Desmond immigrated to Woy Woy in the fifties, that he sat down to write the classic Puckoon overlooking New South Wales-Central Coast. In 2018, Woy Woy Library paid the ultimate compliment by creating The Spike Milligan Experimental Space (SMES), housing a collection family memorabilia donated by Des and son Michael, which includes diaries, photographs and letters between Spike and the Milligan family. ‘It’s an absolute total joy that Spike is celebrated, long may it continue, says Jane. ‘I am sad that Des sold Grandmas house in Orange Grove road; it was an iconic location for all the Milligan’s. Spike was a big supporter of protecting the rights of the indigenous peoples of Australia; he was a campaigner for The Bell Bird sanctuary centre, he found some ancient caves behind the house in Woy Woy. Spike also re-wrote the National Anthem, but it got rejected!’

Receiving an honorary knighthood from HRH The Prince of Wales at St James’s Palace in 2001, Spike died in 2002 at the age of 83, but his Irish wit is still evident with his memorial stone in Gaelic: Dúirt mé leat go raibh mé breoite (I told you I was ill). Spike was uncompromising in his humour, even in death, perhaps serving as a coping mechanism, and his way of laughing in the face of tragedy; ‘The dark outlines are evident in much of his comedic work’ explains Dick Fiddy. ‘Lots of Spike’s humour centres around death and the war. He makes jokes about undertakers and coffins, illness and poverty. Those dark areas prove rich inspiration for him as if he was saying ‘if you weren’t laughing you’d be crying’.

Lá breithe shona duit, Spike.

Spike Milligan | Courtesy of The British Film Institute

Spike Milligan Day will take place at BFI Southbank on May 7th 2018.